The British Museum in London is currently hosting “Manga マンガ”, the biggest exhibition on manga outside of Japan to date. Visitors are presented with a thorough introduction to the medium and its history until August 26th, 2019. Up to late July, the Japan House London had yet another manga exhibition on display. It went deep into the work of a single artist with “This is Manga – the Art of Urasawa Naoki”.

When the international manga boom started around twenty years ago, it was still widely believed that comics are just for children, nerds, and perverts. While Japan, the Franco-Belgian region, and the USA already had a flourishing comic culture that went beyond a pop-cultural, entertaining medium, vast parts of the world either overlooked comic as an art form or looked down on it.

Mimi, a manga character drawn by Fumiyo Kōno, morphing from “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”’s March Hare into a rabbit that draws influence from Japanese fables.

Yet already in 1992, Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel “Maus – A Survivor’s Tale” won the Pulitzer Prize. Telling the story of the author’s father, a Polish jew in occupied Poland and Auschwitz, “Maus” is a prime example of how serious the medium can be. Another outstanding work is “ICHI-F: A Worker’s Graphic Memoir of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant” (いちえふ 福島第一原子力発電所労働記), which was published in Japan from 2013 to 2015. Written and drawn by a worker of the cleanup operations under the pseudonym Kazuto Tatsuta, the manga allows a view inside the disaster power plant Fukushima Dai-Ichi no other means can with photographs being strictly forbidden.

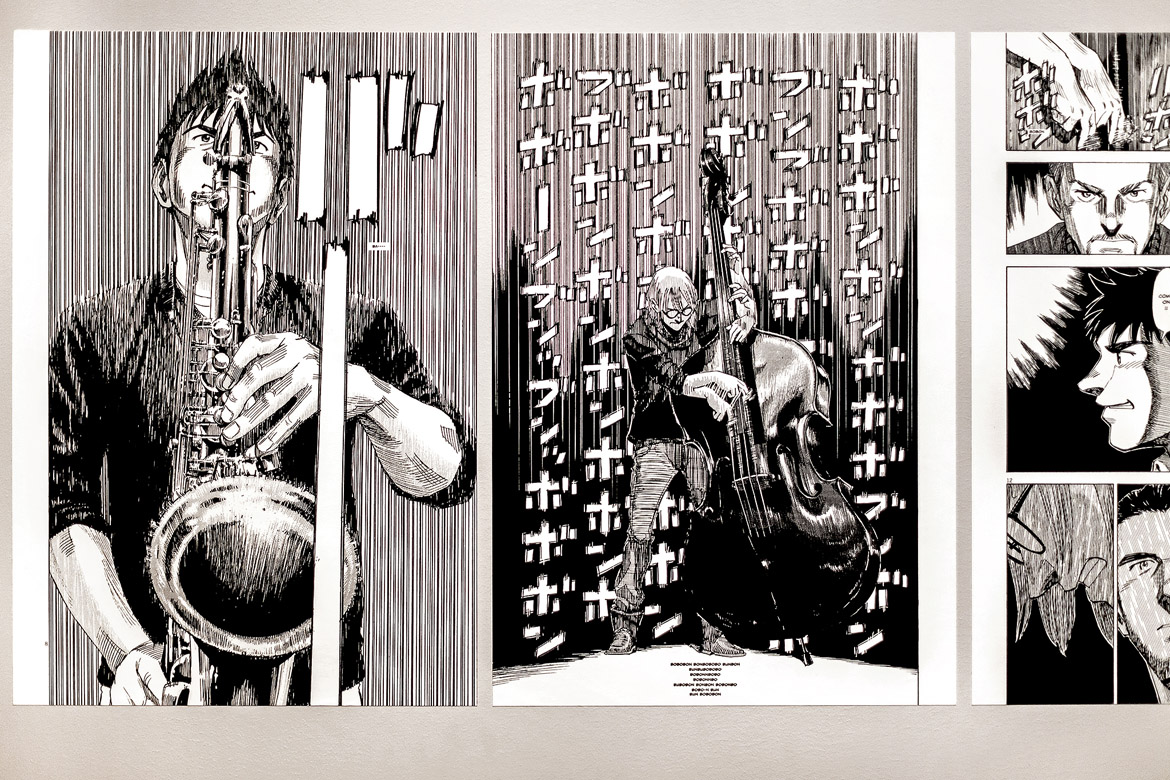

Pages from “Blue Giant Supreme” (ブルージャイアントシュプリーム) by Shin’ichi Ishizuka—an excellent sample for the use of sound words or onomatopoeia in manga, which outdo their Western counterparts by far.

Next of those grave works are countless beautifully written and drawn narrations that carry us away to current events or fictional places. Comics and their Japanese equivalent mangas are means of expression just like novels or movies are. There are good and bad comics, culturally and historically prized ones as well as cheap publications that are merely read and then tossed away.

Comic artist Will Eisner called comics “sequential art” and “graphic storytelling” and the French bande dessinée advocates Claude Beylie and Francis Laccasin coined the medium the “ninth art”. Even the Louvre, probably the world’s most eminent art museum, has exhibited comics and even commissions them since 2005. Yet, even after numerous publications and exhibitions, comics are still widely disregarded as a valuable cultural property.

Kohada Koheiji as ghost of a man, who was murdered by his wife and her lover, from “One Hundred Ghost Tales” (百物語) by Katsushika Hokusai.

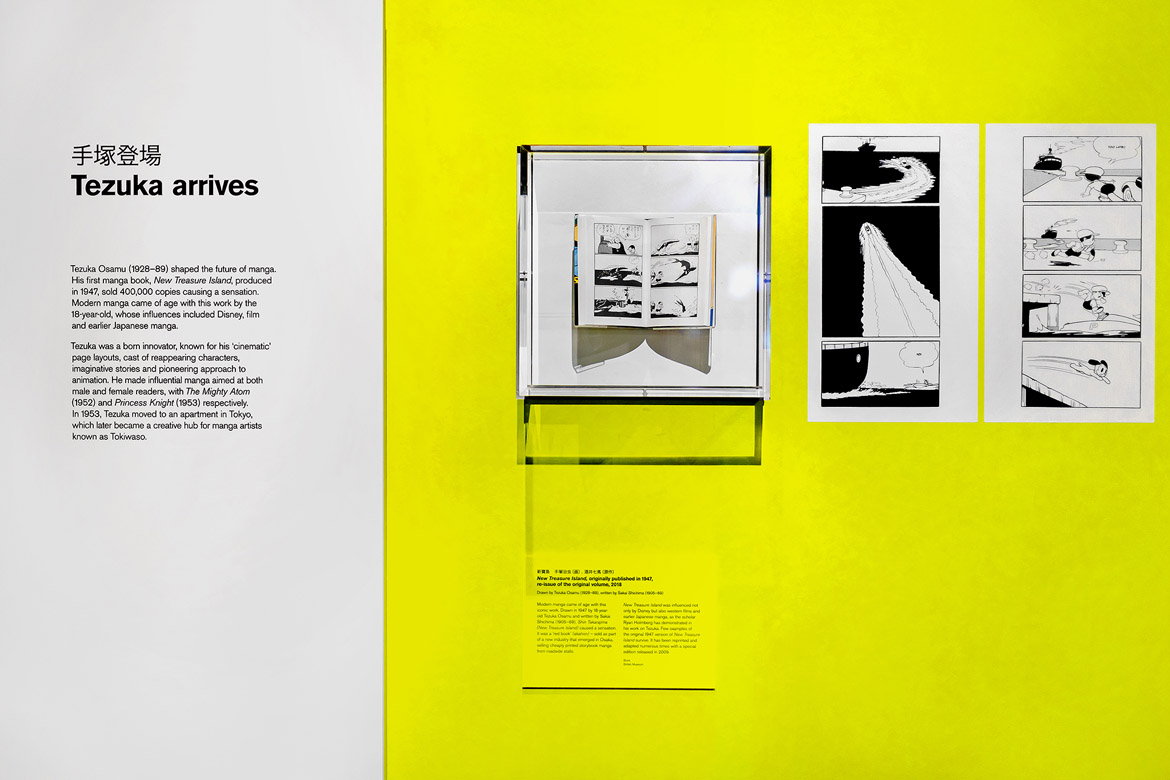

Display about manga legend Osamu Tezuka with samples of his first publication “New Treasure Island” (新寳島) from 1947, which sold 400,000 copies.

It seems like The Guardian critic Jonathan Jones hasn’t gotten the memo either. In his review of the British museum’s Manga exhibition, Manga review – where has all the riotous fun and filth gone?, he comes to the conclusion that “this exhibition is a tragicomic abandonment of a great museum’s purpose.” While admiring the exhibition’s pieces from the 19th century, he considers what manga is today a mass product “on offer everywhere, 24/7”.

In doing so, he reveals his bias against manga and the sequential art while missing the point that the art he adores so much was also created to reach a wide audience. What the British Museum actually accomplishes with its Manga exhibition is the appreciation for the medium. A show like this manifests the significance of comics and manga as a cultural asset and offers a great opportunity especially to those not familiar with it.

British Museum – Manga マンガ

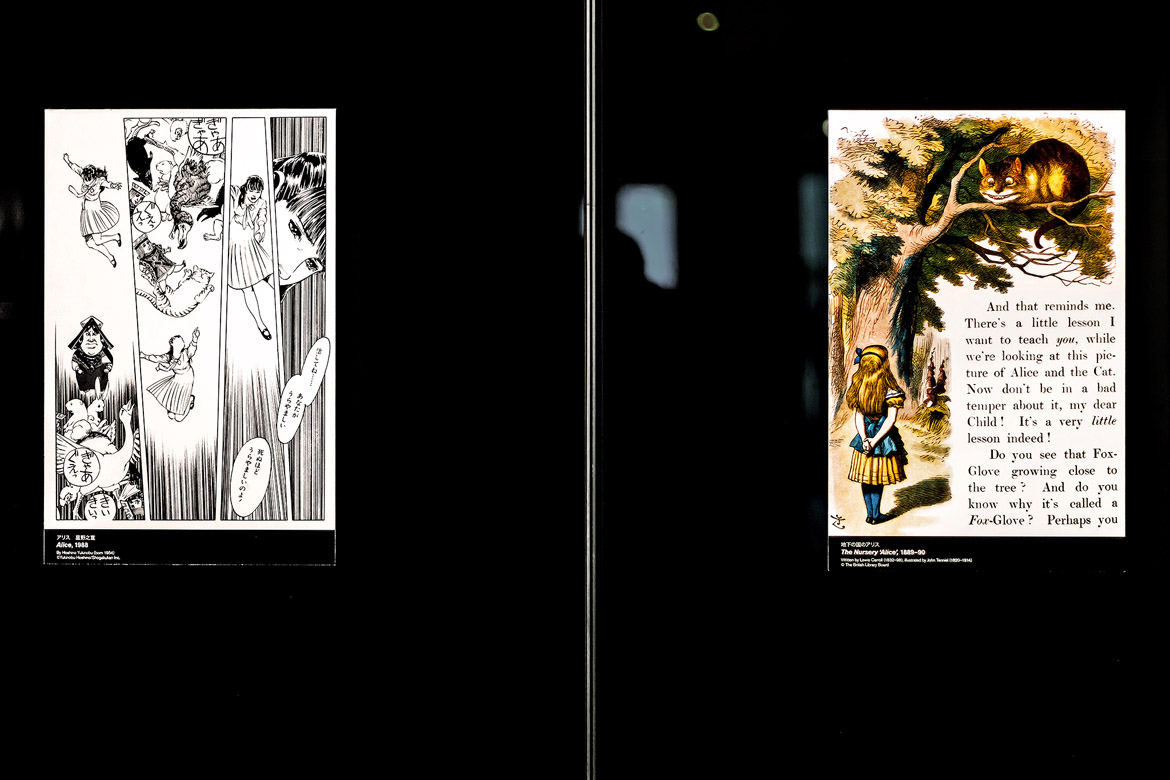

With “Manga マンガ”, the British Museum forges a bridge between its prestigious historico-cultural collection and the present. When entering the foyer of the museum’s Sainsbury Exhibition Galleries space, the visitors are greeted with a few manga adaptions of Lewis Carroll’s famous “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” next to a page of an old British volume. Manga is presented as a world of wonders, where “everything is possible” and by stepping into the first exhibition room, the visitors become Alice falling down the rabbit hole themselves.

Pages of “Alice” (アルス), a manga adaption of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” by Yukinobu Hoshino, published in 1988, and “The Nursery “Alice””, a children’s book version from 1989–1890, illustrated by John Tenniel.

Alice, drawn by Katsuhiro Ōtomo, creator of “AKIRA” (アキラ), from his short “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” from 1980 at the entrance to the British Museum’s manga exhibition.

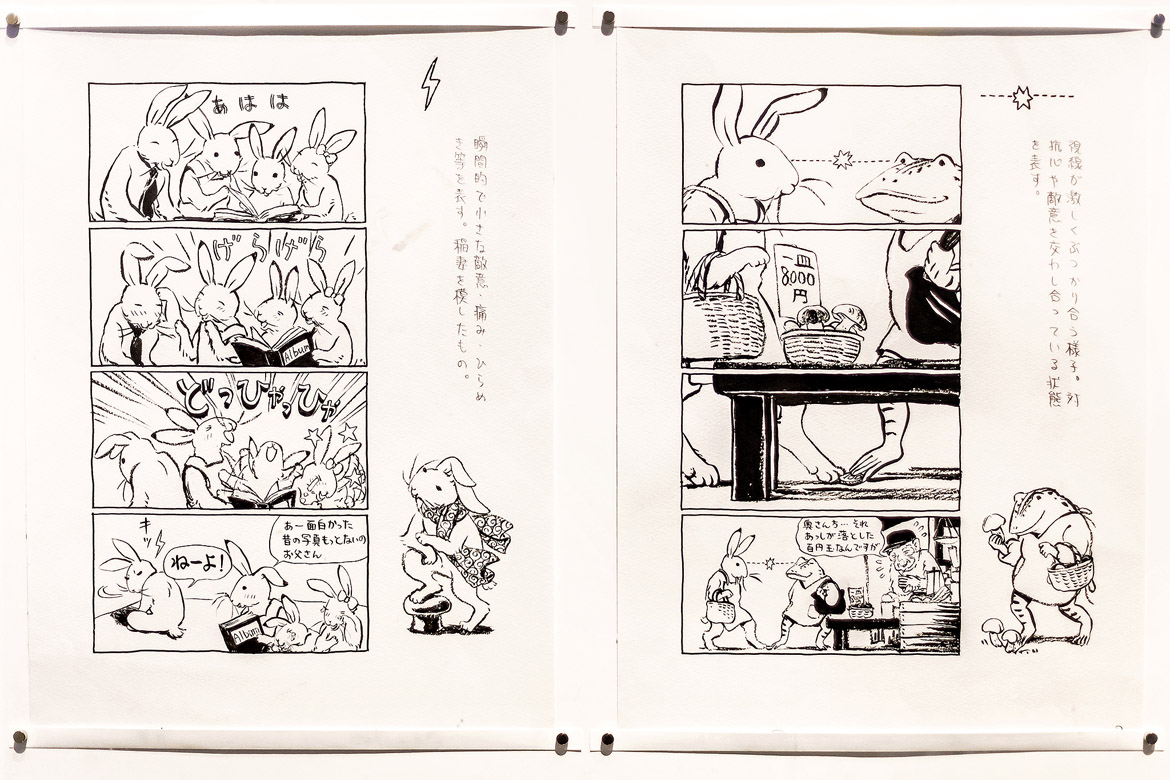

Throughout the exhibition, the curators found the right balance to approach both newcomers to manga as well as die-hard fans. At first, those unfamiliar with the medium are taught to read mangas from right to left. Experienced enthusiasts can skip the lesson while completing their knowledge on manpu (symbols and signs to express movement and emotions) through pages of Fumiyo Kōno’s “Giga Town: album of manga symbols” (ギガタウン 漫符図譜).

Equipped with these basics, visitors proceed to the production process of Japanese comics. They can look at tools and materials to draw mangas, but also view several interviews explaining the structure of the industry.

Original page drawings of Fumiyo Kōno for “Giga Town: album of manga symbols”.

Display with screen tones used to shade manga pages, tools of “SLAM DUNK” (スラムダンク) and “Vagabond” (バガボンド) creator Takehiko Inoue, and an “Illustration Manual of Drawing Manga” (石森マンガ教室) by Shōtarō Ishinomori, who is known for “Cyborg 009” (サイボーグゼロゼロナイン) and “Kamen Rider” (仮面ライダー) among other works.

In the next section, the exhibition explores the history of how manga became what it is today. Visitors are shown that the origin of manga can be traced back to woodblock prints of the 19th century. Not too different from the modern industry, publishers of artists like Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Kuniyoshi competed with tight deadlines and affordable prices, thus reaching a rather wide audience.

The term “manga” first appeared as a book title in “Hokusai Manga” (北斎漫画), volumes with collections of sketches by Hokusai. After Japan had opened to the Western world, the word changed into the meaning of “caricatures” after satire became popular in the 1870s. By the time of the early 20th century, comic strips with usually four panels were established. Then after WWII, the strong cultural impact of America shaped Japanese mangas further with influences such as popular movies and Disney.

Magazines called “Boys’ Club” (倶楽部) and “Girls’ Club” (倶楽部) from 1944 and 1945, which further increased their manga content after the war.

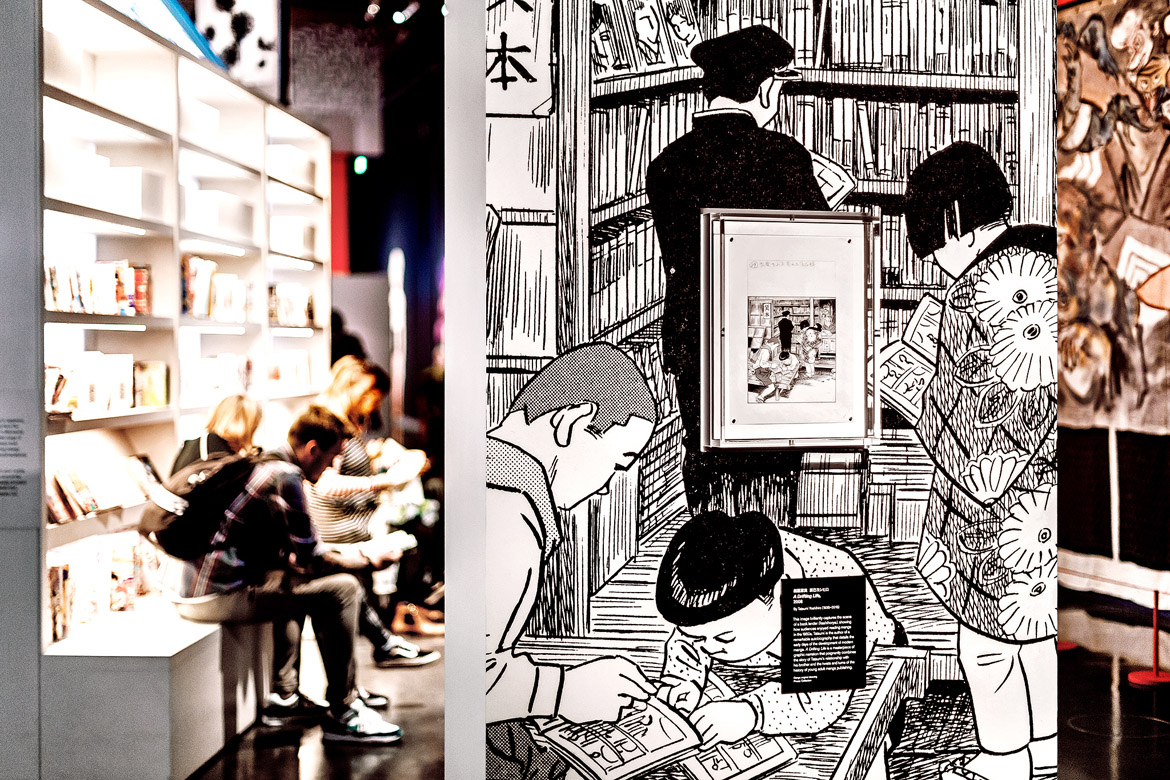

A scene from “A Drifting Life” (劇画漂流) from 2008, the autobiography of Yoshihiro Tatsumi, which is showing a book lender in the 1950s. In the back of the photo, visitors are reading manga in a replica of Japanese bookstores.

Even those who are already quite familiar with mangas and their history like myself can enjoy the exhibition to the fullest. It’s stunning to see the original artworks and rarities. Large photo and graphic prints capture the mood of old book stores and make the history tangible. Right behind lies a small library, bringing the visitors back from the past to the present.

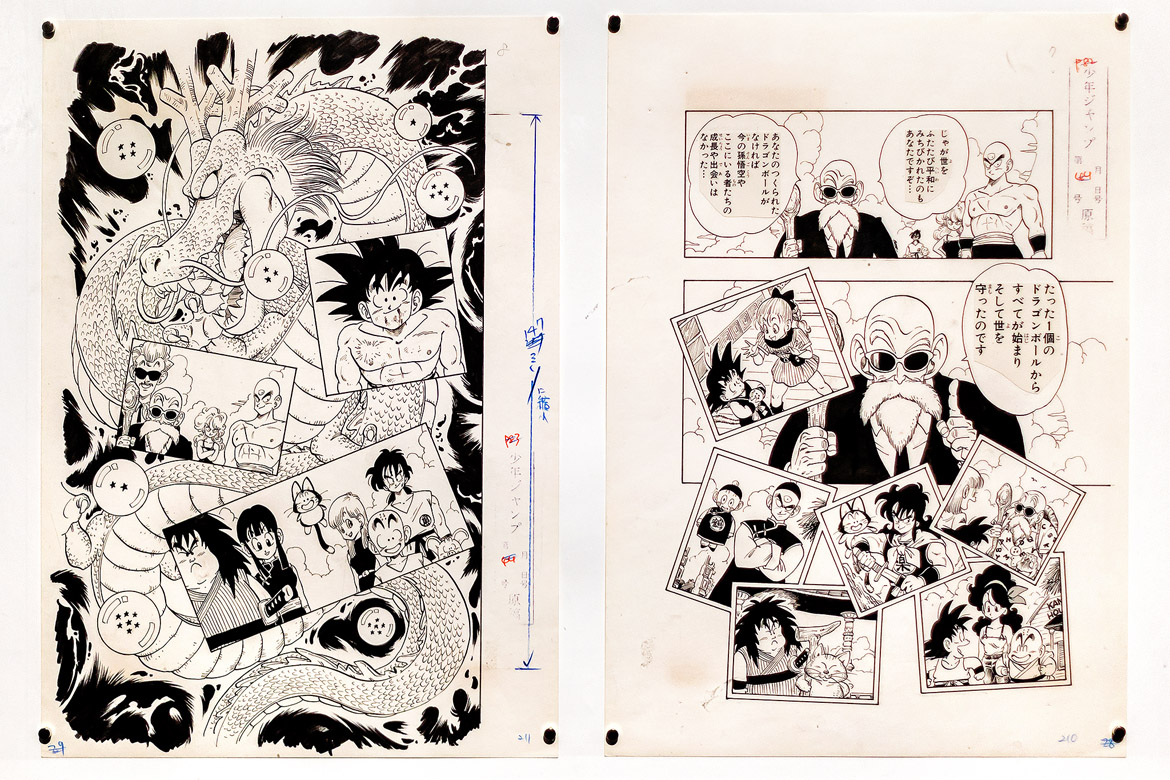

Original pages of “Dragon Ball” (ドラゴンボール) by Akira Toriyama, one of the worldwide most popular mangas. “Dragon Ball” has 42 volumes and ran from 1984 to 1995.

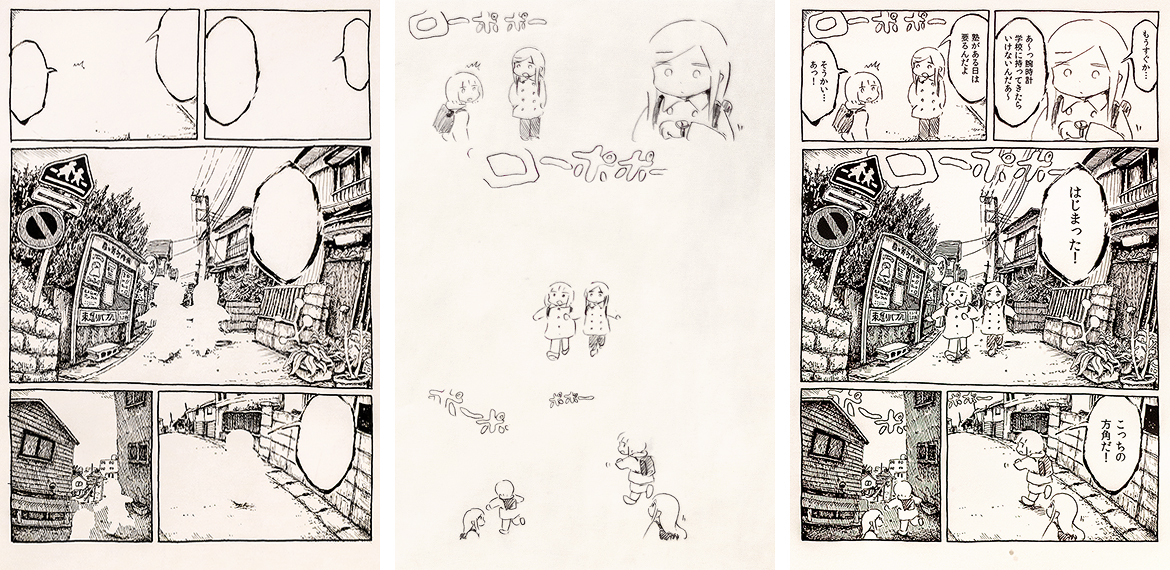

Drawings of “Melody” (メロディー) from “The Second Goldfish” (二匹目の金魚) by the manga artist panpanya. The pages are compiled with the sceneries, which are showing the city Kawasaki, being drawn with a ballpoint pen and the figures being developed in pencil.

Entering the next ‘room’, some of the many subjects in manga are introduced. Ranging from themes like “Love and desire” and “Sports” to more unexpected topics such as “Faith and belief“, the British Museum gives a good overview and makes the point that manga is truly “for everyone”. The selection gives the audience proof of the diversity in manga publishings and makes clear that the scope reaches readers of all interests and ages.

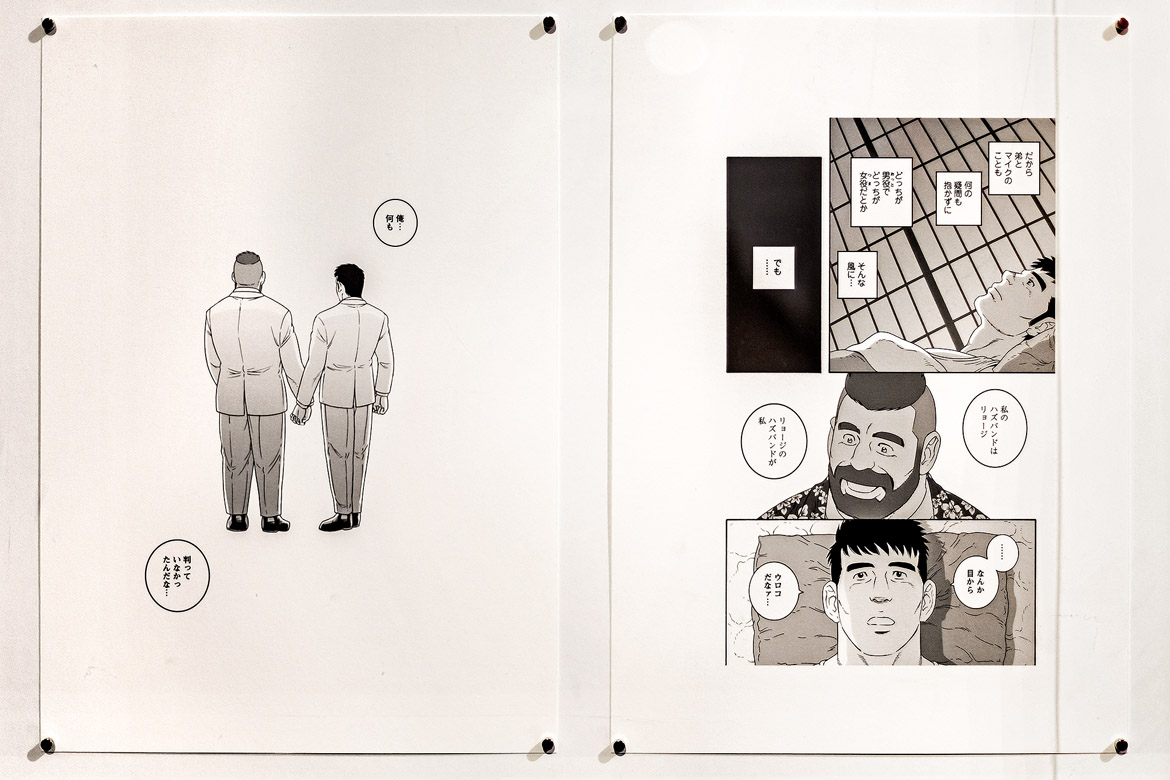

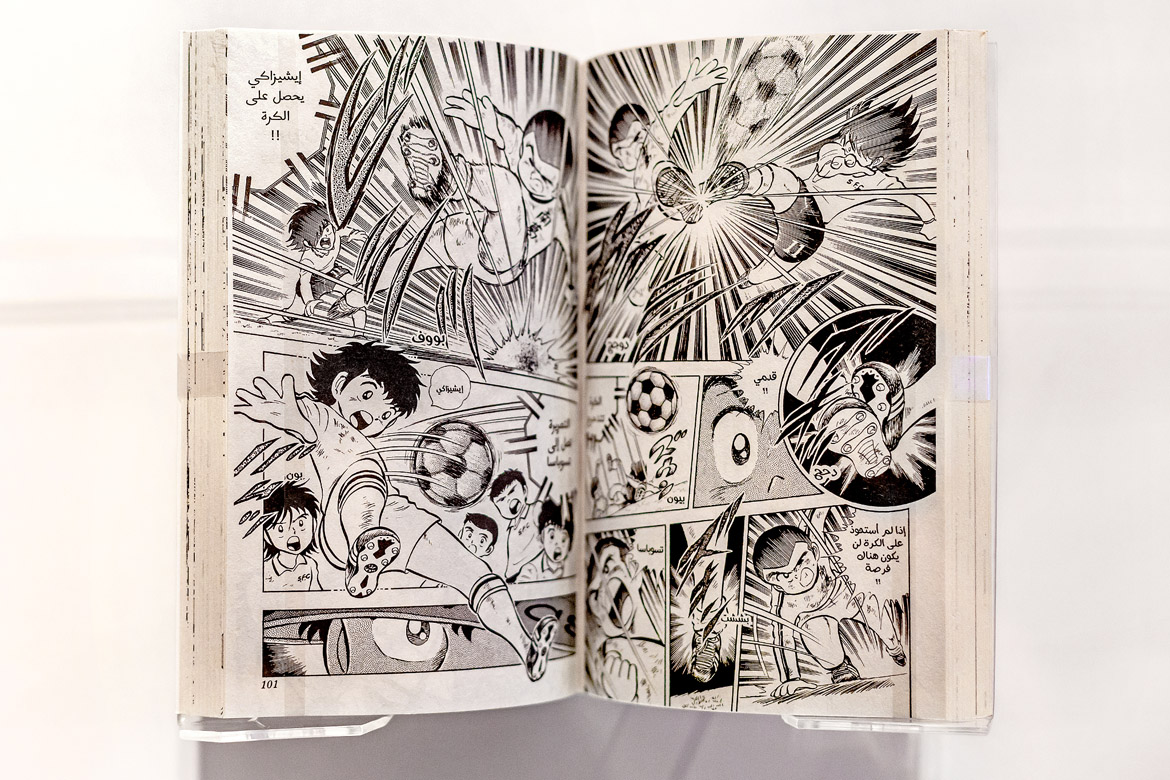

Next to pages from best-sellers like “ONE PIECE” (ワンピース) from Eiichirō Oda and “Naruto” (ナルト) by Masashi Kishimoto hang less famous or mainstream popularity seeking mangas like “Spiral” (うずまき) from horror star Junji Itō. Gengoroh Tagame’s “My Brother’s Husband” (弟の夫) is representing a serious take on homosexuality and homophobia. And did you know, that “Captain Tsubasa” (キャプテン翼) just made a comeback on the North African market and was widely distributed in Syrian refugee camps?

Pages from Gengoroh Tagame’s “My Brother’s Husband”, which was praised for illustrating the subtle, often invisible homophobia in (Japanese) society.

Arabic volume of “Captain Tsubasa” by Yōichi Takahashi, translated by Kassoumah Obada, who watched the anime adaption on Syrian TV when he was a child, not knowing it was actually Japanese.

The exhibition concludes with a view on how manga expands towards animes (Japanese animation movies and series), fan conventions, cosplay (fans dressing up like their favorite characters), and even fine art. Rieko Akatsuka, daughter of famous manga artist Fujio Akatsuka, who is featured in the exhibition as well, turns the sound words of her father’s works into sculptures.

A photo point allows visitors to turn themselves into manga before leaving the exhibition.

Colorful pages of “Rohan at the Louvre” (岸辺露伴 ルーヴルへ行く), drawn by Hirohiko Araki in a commission work for the Louvre.

Though mastering the difficult task to sum up such an enormous subject with skillfully selected exhibition pieces, the objective of the British Museum’s Manga exhibition that “visitors become fluent in manga” is aimed too high. Manga lives from its storytelling through visuals and words, thus making it hard to truly grasp the medium without actually reading at least one manga.

In the end, the exhibition delivers an in-depth introduction into manga, that truly honors the medium. But it doesn’t come close to the full spectrum of what manga can be as the fringes are missing. The selection rather focusses on success stories, but neglects the underground and could, for example, have introduced journalistic works such as “ICHI-F: A Worker’s Graphic Memoir of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant” as well.

Nevertheless, the exhibition is absolutely worth to visit, even though the tickets are quite expensive with prices such as £19.50 for an adult visitor. The exhibits are fantastic and you’ll learn something, no matter how much you know about manga.

Japan House London — This is Manga – The Art of Urasawa Naoki

Entrance to the solo exhibition of Naoki Urasawa at Japan House London with characters of the manga artist’s early work “Yawara!” greeting the visitors.

From early June until late July 2019, London was also home to yet another formidable exhibition on the medium manga. The Japan House London, a modern shop and hub for creativity and innovation, had a solo exhibition of Naoki Urasawa on display.

“This is Manga – the Art of Urasawa Naoki” had been shown at the Japan House in Los Angeles before and allowed a deep dive into the work of one of Japan’s most prolific comic artists. Naoki Urasawa is a praised, award winning manga artist and musician, who was called “a national treasure of Japan” by Pulitzer Prize for Fiction winner Junot Díaz.

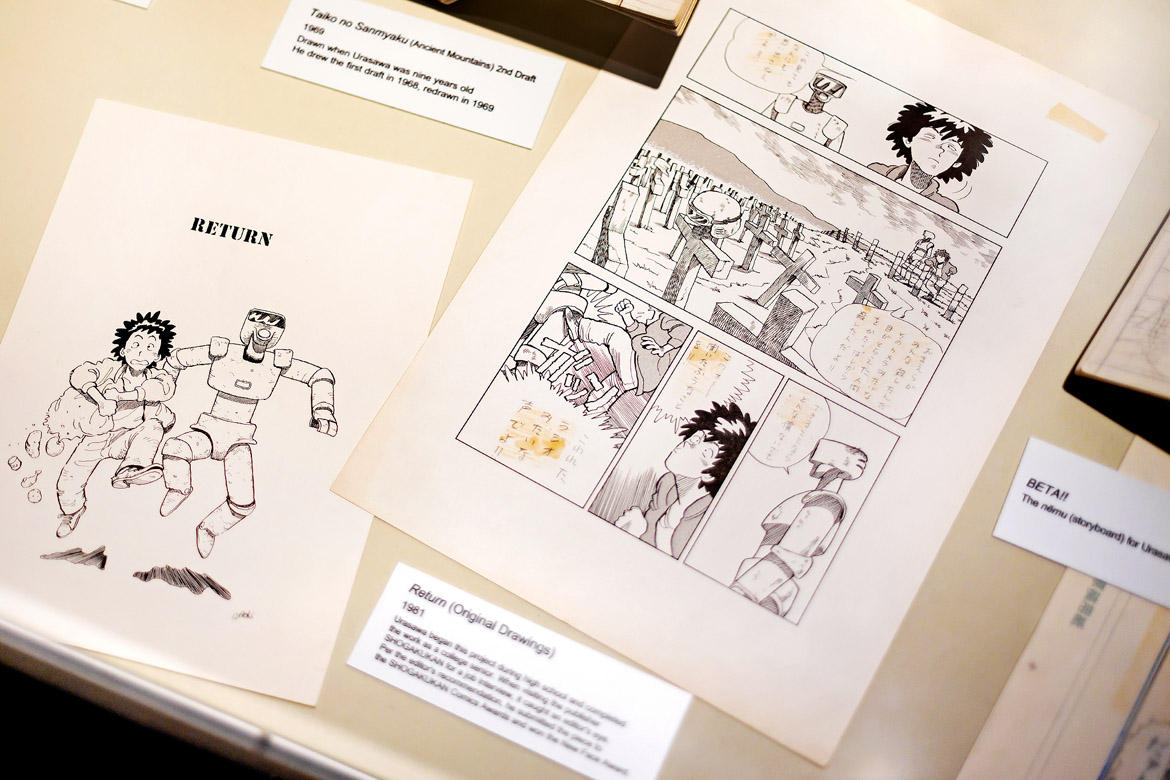

Original drawing for “Return”. Naoki Urasawa started the project in high school and completed it as a collage senior. It caught attention from an editor at Shogakukan and won the publisher’s New Face Award.]

Character studies for “20th Century Boys”, another famous manga series of Naoki Urasawa, which gained world-wide success.

Born in 1960, Urasawa made his professional debut with “Return” in 1981. Working with his own scripts as well as other writers, the manga artist has released numerous stories while usually working on several projects at once.

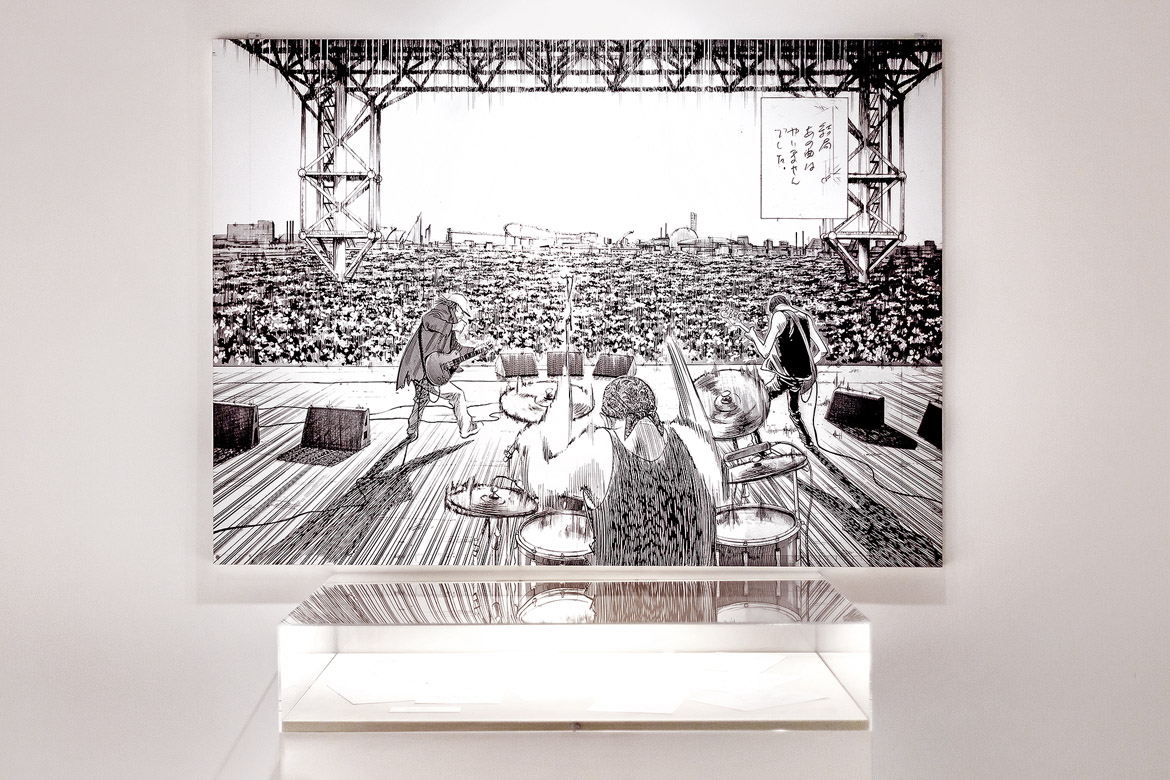

Urasawa’s skilled character design and intriguing stories become greatly tangible in the Japan House’s exhibition. His early manga “Yawara!”, for example, features a young, female protagonist and has an upbeat and entertaining sports theme. Yet since starting “Monster” (モンスター) in the mid-90s, Naoki Urasawa spectrum changed towards suspense-packed thrillers with a cinematic approach through realistic, detailed, and well researched drawings.

Impressions on “Monster”, which was both written and drawn by the artist, introducing a sinister story of a surgeon and a serial-killer in West Berlin. It has been “Monster”, with which the artist accomplished his international break-through.

A panel of “20th Century Boys”, which also illustrates Naoki Urasawa’s passion for music.

Different from the British Museum’s “Manga” exhibition, where only a few single pages were shown, visitors were able to read whole sequences of all of Urasawa’s main works. For “Yawara!”, the pages on display were even changed every two weeks, introducing four stories over the course of the exhibition period.

All storyboards had English translations on top of the original drawings, which allowed visitors to get a true impression not only on the visuals but also the storytelling of Urasawa’s work. Aside of the manga pages, there were sketches, drawings, and illustrations on display, some of which were exclusively made for the London show.

Calligraphy hanging scroll with a drawing of Jigoro Inokuma, a character of “Yawara!”. A few pages of a storyboard can be seen in the back.

One of Urasawa’s vibrant, colorful original drawings and pleasant surprises in the solo exhibition. This illustration was made for NHK ‘professional’ broadcast in acrylic paint on paper.

Exhibitions like this are rare and the Japan House picked a formidable artist to introduce manga even to new readers. Naoki Urasawa’s mangas are published in twenty countries outside of Japan, which makes his work already well known. But it wouldn’t be surprising, if plenty curious visitors left the free exhibition with the urgent desire to pick up a few of Urasawa’s stories to continue the experience!

Extra: Japan House London Library—LGBT+: Diversity in Manga

Display in the Japan House London’s Library, showcasing the diversity of gender and sexuality in manga.

In the closure of this article, the display on LGBT+ themes in manga should get a mention. It’s been part of “Pride in London 2019”, which celebrated the 50th anniversary of the modern LGBT+ rights movement with several events throughout the city such as a blasting parade on July 6th.

Some works such as Gengoroh Tagame’s “My Brother’s Husband” as well as “Princess Knight” (リボンの騎士) by Osamu Tezuka with a gender-bending main character and “Princess Jellyfish” (海月姫) by Akiko Higashimura, which features with cross-dressing male character, are also featured in the British Museum’s “Manga” exhibition.

But the Japan House London’s Library went further and deeper. A collection of several mangas with LGBT+ topics reflected how gender norms were questioned in the past seventy years. Many stories might be perceived as pure entertainment at first but are in fact “helping to challenge and soften stereotypes and often rigid social norms in the somewhat conservative society of Japan” as the announcement put it.

Guests could browse through the display with a few introductions to a few subjects such as transgender and homosexuality in manga. By picking up books from the shelves and sitting down in the small, bright library room, they were able to receive an individual impression. What a fine way to create recognition for LGBT+ matters and mangas featuring them.

Bravo, London, and thank you for your brilliant contribution on the perception of mangas and comics and their acknowledgement as a form of art!