The installations of Chiharu Shiota have an air of mystery about them, whereby one has the strong impression of taking a glimpse into another person’s subconscious – or are they your own dark dreams you almost forgot about? This portrait of the Berlin based, Japanese born artist explores her approach in addition to what it means to her to live and work in Berlin.

Shiota was born in Kishiwada in Osaka. Her parents were owners of a small factory which produced wooden boxes to transport fish.

“I always saw the laborers in the factory, working like machines. I wanted to choose a different path, something more spiritual.”

At first, Shiota wanted to be a painter. But when studying, she reached a point when she realized that every subject she could think of, every way to paint, had already been done by other artists. She changed her approach by incorporating herself into the artwork, painting with her own body.

Other female artists like Marina Abramović, Hannah Wilke or Valie Export who developed similar approaches in the 1970s come into mind. But still, this wasn’t enough for Shiota, this wasn’t what she was looking for.

“I wanted to choose my own material, something which allowed me to be myself. So I started working with woollen threads.”

After her graduation from Kyoto Seika University in 1996 she left for Germany and began to experiment with materials. Consequently, during her postgraduate studies at Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Hamburg she created in 1997 an artwork based on animal skulls,

In the inner courtyard of the Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Shiota placed a group of bovine skulls on the lawn, huddled around a cluster of chicken eggs like a flock of gruesome birds around its nest. Some skulls still have traces of blood on them, on the bottom side the spectator can see teeth sticking out. The arrangement may have its background story, but to acknowledge the erie charm, it’s not even necessary to be aware of this – the mysteriousness is one reason why Shiota’s art is so fascinating.

In 1997 Shiota began her studies with Marina Abramović, the prestigious performance artist, by a strange series of events. Wanting to apply to study with Polish textile artist Magdalena Abakanowicz, she wrote a letter – but as the pronunciation sounded just too similar to Abramović’s name, it was sent in error to her. Or maybe the recipient was actually the right one, as fate will…

“Marina was always an artist to me, never a teacher. We were very free as students.”

Marina Abramović is one of the most interesting contemporary performance artists. Born in Serbia, she started her work in the 1970s, exploring the boundaries of her body, of pain and the relationship between her as the performer and the audience. She became a pop cultural icon as evidenced by her performance at the retrospective of her work at Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in 2010, “The Artist Is Present”. She was – as the title says – present at the exhibition and visitors could sit down across from her and hold eye contact for a certain length of time. In 1999, Shiota moved to Berlin when she began studying with artist Rebecca Horn at Universität der Bildenden Künste.

Today, Chiharu Shiota’s work centers around her concept of “Existence in Absence”, as mirrored in experiences of loss and tragedy, arising from dealing with historical and personal circumstances. Abandoned objects are a central element of her work, things which belonged once to somebody, are not needed anymore and given to the artist by request. They show by their worn appearance how heavy with memories, hopes and disappointments they are. This could be shoes as in “Dreaming Time” (1999) or in “Dialogue from DNA (2004), Photos in “My Cousins Face” (1998), dresses in “Memory of Skin” (2001) or windows as in “From-Into” (2004) and “House of Windows” (2005). In particular, windows and dresses are recurring objects. Woolen threads which interweave and enwrap the objects are the foremost striking material. In red, they remind one of veins, of blood transfusion tubes or provoke associations of cobwebs when they are black.

“I like Ana Mendieta. There is a female side to my art, female labor is a topic which interests me as well. But I wouldn’t say I am a feminist. The community spirit and the emotional side are important to me.”

Shiota leaves the interpretation of her artworks and performances to the audience, although she is open to talk about sources of her inspirations. But experience shows that her art is so intensively thought provoking that most people immediately draw connections to their own lives and memories immediately. The threads entangle not only seemingly abandoned objects, but our own minds as well. We can’t defy their appeal and the dramas hidden within them as we realize that what we find are our own fears and traumata.

A striking example is her installation “Dialogue From DNA”. Shiota asked people in Poland to donate their old shoes to her and enclose a message which told what these shoes meant to them. To the audience in Poland, the connection to Auschwitz was immediately clear, as pieces of clothing often were the last traces which could be preserved of the people murdered in the concentration camps. Shiota herself didn’t intend that, but doesn’t mind the differing interpretations:

“I showed the installation with the shoes in Krakau, Poland and people there thought immediately of Auschwitz. When I showed the same piece in Osaka, nobody thought of Auschwitz. Everybody sees it different. I work a lot with memories, and for many people memories are about death. The keys [used in “The Key In The Hand”, 2015] weren’t new keys, but old, rusty ones. For somebody, these keys keep a memory, but the person connected to it aren’t there anymore. It’s similar with shoes, clothes something you wear every day. Objects can be like a photo of someone.”

Shiota developed the installation “Key In The Hand” for the Venice Biennale 2015, when she was awarded with the Design of the Japanese Pavilion, one of the highest honours an artist can receive today. The installation featured four screens showing videos of children answering questions about what they believe to remember of their birth. In the next room, Shiota placed two fisher boats in an entanglement of red threads from which a myriad of rusty keys dangled, part of them lying on the floor. In the photos, the boats are hardly visible from some angles as the network of threads is so thick. Keys have a spec ial meaning in the Western World, as keys are seen as essential for having a home – an abandoned key creates the impression that there has to be an abandoned house somewhere.

Living in Berlin for more than 20 years has its influence on Shiota’s art. The Berlin Wall is a recurring topic as well as the relations between people in the former eastern and western parts of the city.

“I moved to Berlin in 1997 – the city was very different then. The energy was different. I lived in Mitte, a lot of houses were in a very bad state. Wenn I’m somewhere for an exhibition and return to Berlin, every time I think, ahh, I’m finally back. When I return to Berlin, that feeling of belonging is immediately there. When I have exhibitions in Japan, I am the Berlin artist or the foreigner. But when I have exhibitions in Berlin, I am the Japanese artist. Actually I am very happy to have both places as a home – I have a single exhibition in Japan at Ginza 6 Shopping Center and in Germany I am going to be part of a big exhibition at Martin-Gropius-Bau. I feel home in both places. I couldn’t say which feels more home to me: Germany or Japan.”

“House of Windows” is an installation from 2005, then on show at Haus am Lützowplatz and was the first artwork of Chiharu Shiota I have seen myself. In the crowded room, a house made of old windows took up almost all the space, a house inside a house. The overlapping window panes filtered the light of the bare lightbulbs inside. Even without knowing that the windows came from demolished houses in East Berlin, one felt the weight of memories coming with all old objects. Automatically, you begin to wonder what these windows might have seen – war and peace, despair and hopes. I was deeply impressed but forgot about looking up the artist until I later on realized that it was the same artist who built the giant thread structures. The windows bring up the for many East Berliners difficult experience to see real estate developers come into their neighbourhoods and tear down old houses, replacing them by new ones or refurbish them into pricy lofts which are not affordable for the former residents.

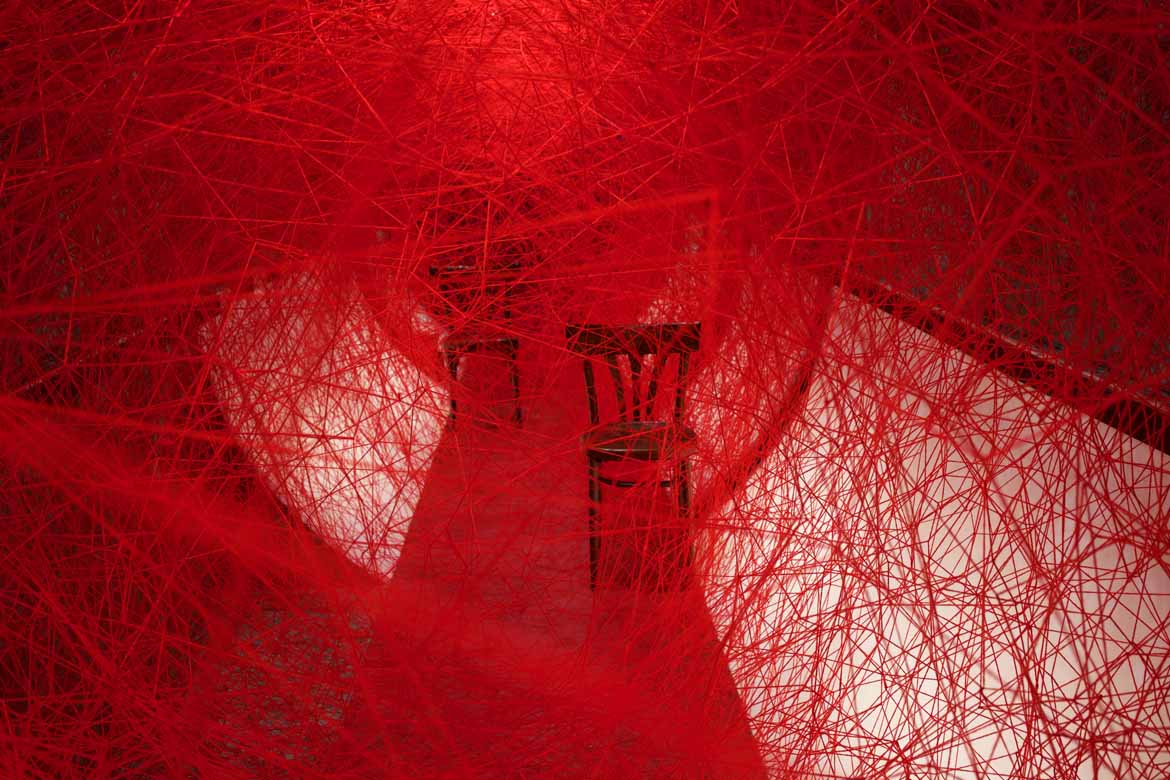

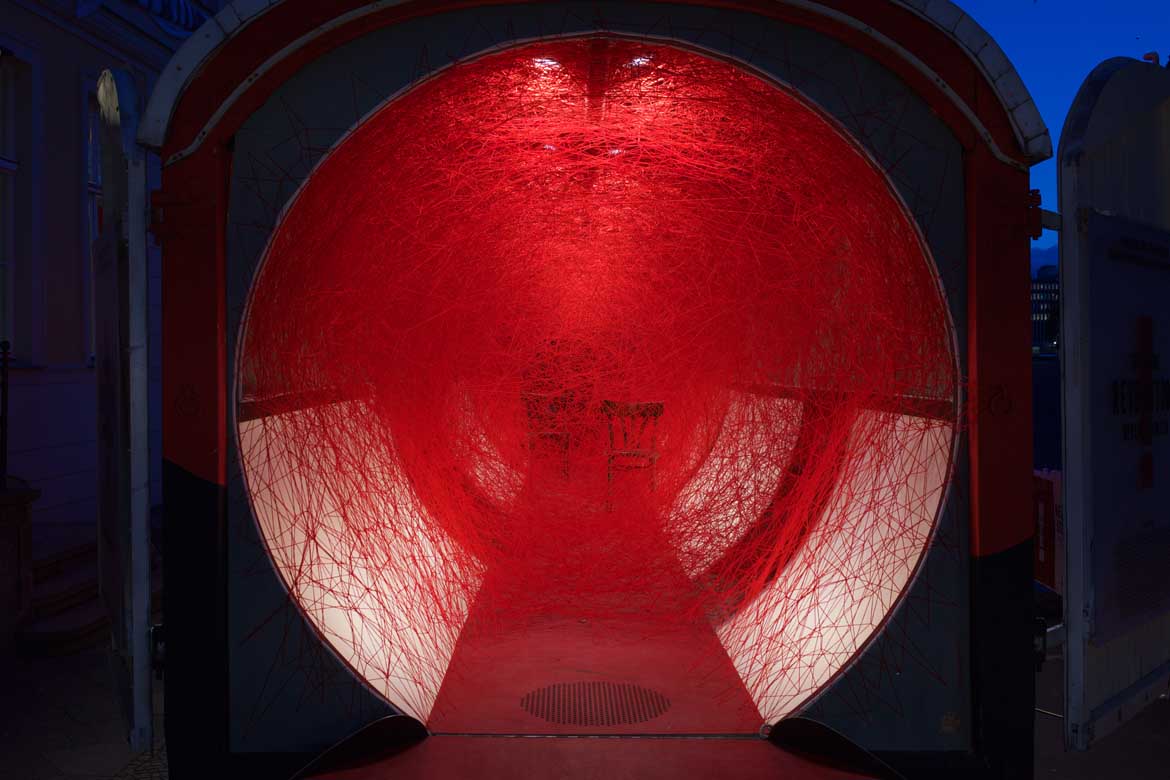

Shiota’s most recent Berlin artwork “Lifelines” is currently displayed at Podewil in Mitte. It is part of an exhibition project remembering “100 Years of Revolution – Berlin 1918-19”. Shiota worked in a historic removal van, as the revolutionaries used them to build barricades in the streets. The vehicle is open at both ends, so it can be accessed from two sides. Inside you find Shiota’s distinctive red threads, spanning from wall to wall and almost enclosing two black chairs in the middle. At the times below are performers occupying the chairs, though they weren’t present when I was there during the opening times. The artwork reminded me of discussions in which opposing political views are debated – the chairs are not facing each other, but placed side by side, facing in different directions. In this instance, the threads didn’t connect something in the first place, but filled up the van almost entirely. The blood shed by people fighting for their rights? They sacrificed so much not only for society then, but as well for us, for the lives we can lead now.

In February, the performance is presented every Monday from 6-7pm. From March 2-10, you can see it at Alexanderplatz, daily from 3-5pm.

Chiharu Shiota’s work epitomizes some of the existential challenges of our time: How do we deal with loss and haunting memories when rituals and religion which helped our ancestors ease the burden have lost their meaning? We should be curious about what there is to come next from Chiharu Shiota.

Kindly, the Japanese-German Center Berlin made it possible to interview Chiharu Shiota. Her quotations are set in bold in the text.

Sources

“An Interview with Chiharu Shiota” by Andrea Jahn (Stadtgalerie Saarbrücken, 2016)

“Mit Haut und Haaren: Der Körper in der zeitgenössischen Kunst” by Marina Schneede (Köln, 2002)

Website of Chiharu Shiota

Header Picture

Lifelines, 2019

old freight wagon, red wool, old chairs

group exhibition: 100 Jahre Revolution 1918/19

Kulturprojekte Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Photo by Sunhi Mang

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2019 and the artist

Picture 1:

Chiharu Shiota

I Have Never Seen My Death, 1997

Installation: bones, eggs

Hochschule für bildende Künste, Hamburg, Germany

Photo by Chiharu Shiota

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2019 and the artist

Picture 2:

Chiharu Shiota

Dialogue From DNA, 2004

Installation: old shoes, red wool

Manggha, Centre of Japanese Art and Technology, Krakow, Poland

Photo by Sunhi Mang

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2019 and the artist

Picture 3:

Chiharu Shiota

The Key in the Hand, 2015

Installation: old keys, wooden boats, red wool

Japan Pavilion at 56th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy

Photo by Sunhi Mang

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2019 and the artist

Picture 4:

Chiharu Shiota

House of Windows, 2005

Installation: old wooden windows, light bulbs

Haus am Lützowplatz, Berlin, Germany

Photo by Sunhi Mang

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2019 and the artist

Picture 5

Lifelines, 2019

old freight wagon, red wool, old chairs

group exhibition: 100 Jahre Revolution 1918/19

Kulturprojekte Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Photo by Sunhi Mang

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2019 and the artist

Thank you <3