Overall I spent nearly two years in Japan. 5 months of that I’ve been traveling the country – usually off the beaten paths. This is the first part of a series of travel stories, insights into people and culture, and weird things that happened to me in this amazing country.

When I did my first big travel in Japan, I was three months on the road. Back then, in 2010, Japan was not as shut off from the rest of the world as it used to be under the Tokugawa shogunate, but tourism has skyrocketed during the last years, and went up an incredible 350% since my first visit. So to say the least, I was quite the attraction wherever I went. Especially because I ventured (partially due to my small wallet) off the usual tourist routes. Hitchhiking my way from Tokyo to Kyushu, couchsurfing in Osaka, sleeping in manga cafes in Shikoku, taking night ferries and taking a road trip around the Amakusa Islands, to name a few. It was the first time in my life that I was free to do whatever I felt like. To go wherever my feet carried me, free from the shackles of family, school and jobs or any other responsibilities. It was a complete and utter feeling of freedom!

At some point on my travels I exchanged that freedom for the loving care and hospitality of a Japanese family that took me in for 3 weeks to help out at their ryokan (Traditional Japanese hotel). The hotel was hidden in the mountains of Kyushu, close to the famous Mount Aso (one of the largest active volcanoes in the world). The only catch was that the hotel was so remote that there was nothing close by apart from Mount Aso. The next shop was a twenty-minute car ride away. But well, there was a private hot spring in the house that the whole family used as their shower when the guests had finished.

As I grew accustomed to Japanese inaka life (inaka means “countryside” in Japanese, but pretty much means “hick” from a Tokyo perspective) the days did not pass by in utter monotony as one might have expected. Instead, they were packed with surprises nearly everyday, often caused by my host mother’s habit of completely shunning the idea to tell me what was planned for the next day. When I got up in the morning, expecting to help with breakfast and cleaning the guest rooms, it was quite possible that, instead, I was told to put on my shoes and then got a private tour around Mount Aso by a professional guide. One night, instead of catering the guests, I was told to sit down and drink sake with them, a group of elderly Japanese men who in their drunkenness then wanted to cheer to the axis-powers and “our” common defeat…

The invitation

Looking back, I therefore definitely could’ve read the signs when my host mother asked me to have “a little talk” about my travels in front of my host brother’s class in school. Being treated so kindly and taken in by a group of strangers, it was out of the question to recline. Since I was quite confident in my Japanese back then, I didn’t expect it to be a big of a deal to talk in front of a few fourteen year olds and shrugged it off with a strong mochiron (“Of course” in Japanese). I was then handed a little piece of paper with 5 or 6 topics that I should talk about. I looked at it briefly and thought, “no problem, easy-peasy”, and went back to drinking beer with my host father. This had become quite the ritual that we drank half the beer tap every second night, and when we were drunk I went to bed, and he went to watch Naruto.

The next morning I was hungover when my host mother woke me up to go to school. That was that with the no family-, no responsibility-, no school-business. I remember quite clearly, how I sat in the lobby scribbling down some notes on a little piece of paper with some questions on it that I got from the teacher, frantically checking words in a dictionary. I was maybe halfway through when my host mother had to pull me off the leather couch and put me in the car. Sitting there, I continued for a little while, but then thought that there was no reason to stress myself and I would just improvise the rest.

The sun was already towering bright over the mountains when we arrived at the chuugakkou (Japanese Middle School for 10 – 14 year-olds). Also, the school was in the middle of nowhere, nothing around but the green, sleeping volcanoes of Central Kyushu. As to be expected in Japan, my arrival was already well planned out. Two teachers greeted me in front of the entrance. One can only guess how long they must have been standing there, and maybe that was the reason why my host mother had rushed me. One of them was a butch looking female sports teacher with a short haircut and a jumpsuit, whose little piece of paper I kept safely in my pocket. With little to no introduction my host mother succinctly wished me a lot of fun and I watched her car drive away into the distance via a little mountain path.

The school principal

I followed the two teachers inside the school that looked like most schools in Japan: a quickly raised, grey concrete block more like the psych ward of a jail than a place for teaching children. But once you go inside, the interior is not a run down, chewing gum infested dark back alley like the school I went to, but a pleasant, bright and clean learning facility. The walls aren’t plastered with graffiti, but with impressive art pieces that are testimony for the children’s creativity.

I hadn’t even properly passed the first door when the sports teacher gently pointed me to my left, and led me into a spacious office. It was no other than the school principal’s.

The principal, a slender and quite tall man, smiled at me welcomingly and offered me a seat whilst speaking in very long overly polite Japanese phrases. As I did not anticipate, that I would meet anyone else than my host brother’s classmates, I thought this would be only a short hello-and-then-off-to-my-presentation kind of thing. But the principal took his time to interview me about my travels, how I came to this school, my host family and what I thought of Japan. Still a bit nervous (and hungover) I tried to answer his questions as well as I could. Still I got a little suspicious. It all sounded a little too familiar to what the sports teacher had written on her note. But that surely was a coincidence.

The journalist

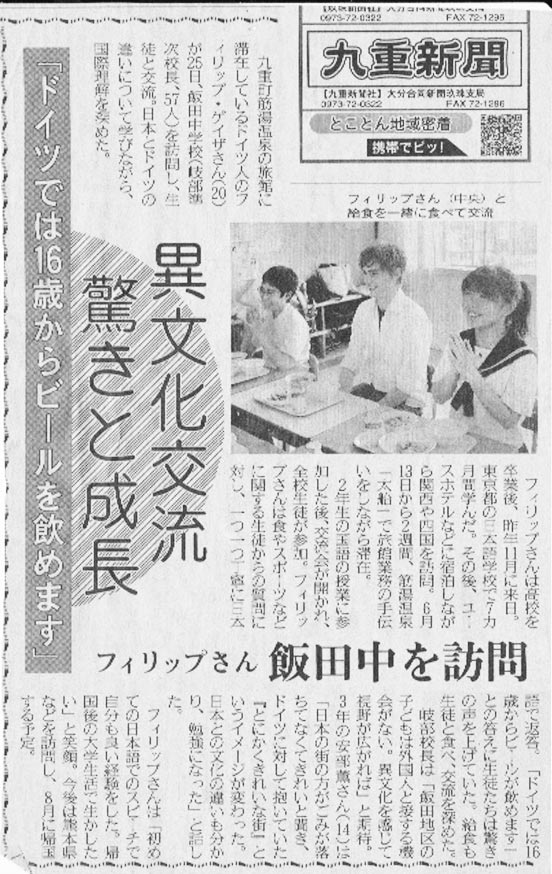

When we finished our conversation the principal smiled at me again. There was just one more little thing, but of course only, if I wanted to, but if I didn’t mind, there was someone from the local newspaper who came all the way to speak to me as well. So if I did not mind, I could talk to him as well? How could I recline! The news reporter came in and took out a little note pad, that he put down in front of him, but never wrote a single word in. He then asked me about my travels, how I came to this school, my host family and what I thought of Japan. Feeling a little bit like in a rote learning exercise in my Japanese class, I told him exactly the same things I had already told the principal. But as my hangover got a little better, I added the fun fact that in Germany the legal drinking age for beer and wine is sixteen, which is always very fascinating to most Japanese people I talked to.

The class

After the interview I was again not led to my host brother’s class, but instead lead through the teacher’s lounge. I felt a little bit like I was trapped in a Kafka novel. Every time I anticipated to finally hold my little speech something unexpected happened and I had to manoeuvre a new situation that everyone totally prepared for, but I hadn’t. So you can guess how big my disappointment was, (and by then my level of confusion), when I finally reached my host brothers class and they just continued with their normal Japanese lesson.

As I sat on a way too small chair next to two really shy, half-my-size school kids, I started to wonder if maybe I had misunderstood my host mother. Did they just want to show me the school? It surely was a very humble Japanese way of making me feel like a special guest, but never forestalling the next step, because I could get bored being only in a middle school. But the opposite was the case. I had a great time getting such a first hand look on Japanese school life. Seeing how they teach in class. Learning that the myth of total ex-cathedra teaching is only partially true. I got so excited that I even thought about raising my hand, when I knew the answer to a conjugation question, but very quickly abandoned that idea, because it might have been a bit stupid to compete with a group of fourteen year old kids in their mother tongue. And whilst I tried wrapping my head around all of this, I got a lot of very cute, giggly looks, when the kids thought I would not notice. My speech seemed to be not on the table for some time.

When the gong rang I had spent nearly four hours in the school and thought it was time for my initiative to just get up and start talking before they forget about it. The Japanese teacher, barely older than me, reassured me that I was going to talk after lunch. So lunch came, and I tried to make a little bit of small talk with my two neighbors. All I got was pretty much cute smiles and giggles again, so I started to feel a bit unsure about my language skills. Did they even understand me? I had another look on my half-heartedly scribbled piece of paper. It was definitely not the lunch, (which is amazingly tasty and healthy in Japanese schools) that now made me feel uneasy in my stomach area.

The gym

The uneasiness quickly rose from a little itch to an ache, when the sports teacher clandestinely put her head through the door to check if everyone finished eating. Then we got up and left the classroom, which was weird, because I thought that classroom was where I would talk about my travels and how I came to this school and stuff. Walking through the school corridors, I saw another class passing just in front of us. As we entered a long glass corridor that seemed to connect two separate buildings, it started to dawn on me what might happen. I glanced worriedly to the sports teacher, which she only answered with a caring smile that you would give to someone that has to jump without parachute before a plane crash. The end of the corridor was approaching and I kept a tight grip on my little note as I saw that we had reached the school gym.

On the gym’s left side were twenty to twenty five chairs set in a row. Most of the faculty had already arrived and taken their seat. The principal was there and even the guy from the newspaper was still present. About three hundred children aged from 10 – 14, were sitting on the floor. In the front of them all was an empty podium that, I then finally concluded, was for me to give my “little speech”.

With four hundred eyes looking at me and only a sweaty paper in my hand, it was quite clear that I was completely underprepared to hold a speech in Japanese. A stuttered piece of gibberish about my travels, how I came to this school, and my host family followed. But everyone listened politely to my mumbo jumbo that went all over the place and barely made sense. When I finally finished a huge silence soaked the room. Then the sports teacher jumped up and tried to activate the masses. Apparently they had prepared questions in class and a very shy child after another stood up to ask me a question, eagerly learned by heart. Seeing the children being even more nervous than I was, I regained some confidence. A girl asked me what my favorite anime was, another if I had a girlfriend. Someone wanted to know if we only ate potatoes in Germany and another asked if we also had bunnies in the moon. In between questions the sports teacher had to jump around and motivate everyone to speak up and then repeated the question again to make sure that I had understood.

The perspective

Although my host family and the school created a rather, let’s call it, special situation for me by not really telling me what’s going to happen, it seemed now as if they had made sure to make exactly that situation as comfortable as possible for me. Even the interview with the principal now seemed like a pedagogic measure to prepare me for my talk. As practice (or a test) so to speak. Whilst I was left with a kind of weird feeling of being exposed and presented like an exotic animal from a distant planet, the lengths this whole school went to just to let some random, traveling German guy talk about his country and his travels was quite endearing.

In a small village in Bavaria a traveller from Asia would surely not get that form of treatment. We would pride ourselves in being so tolerant and cosmopolitan that we do not need to show any interest in other cultures. It showed that the concept of foreignness in Japan is a very different one from the one we have in Europe. It is actually connected to a curiosity and a genuine interest to learn first hand from people coming from different cultures.

As these kids were barely in touch with people from other countries, the school must have seen a chance to widen their student’s horizons and give them a chance to think about things they usually do not think about. So if someone ever seems intrusive in Japan because you are a foreigner, you can rest assured that it is driven by a genuine interest in you as a person. And if you go along, you will very likely have an amazing encounter and might even learn something about yourself.

The article

So I could not wait for the article that was written about the cultural and pedagogic missionary deed I had done. Two days before I had to leave my host family to continue on my adventure the article finally arrived! The headline was quite sobering. It said in big fat bold letters: “In Germany you are allowed to drink beer when your sixteen.” That’s what they remembered from my visit.