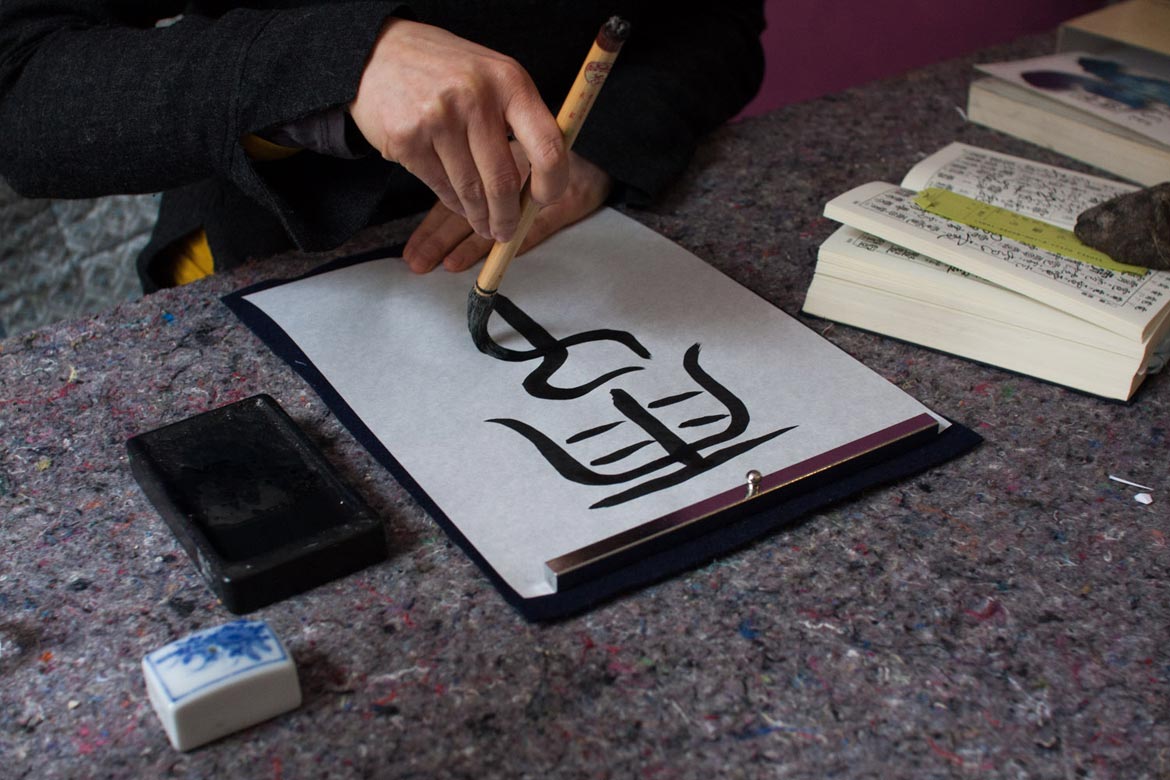

As head of Sosekido shodo school, Juju Kurihara connects people of all ages and backgrounds with a creative approach to the art of Japanese calligraphy. She spoke with us about her personal journey and how her work in Berlin is inspiring others in Japan to break free from tradition.

How did you get into shodo?

When I was in primary school we had the option to take music, art, or calligraphy class. I didn’t like music because I didn’t like singing in front of others, and I didn’t like drawing—now I do, but at that time my drawings were horrible. (laughs) I didn’t know what calligraphy was, and thought I would just take it.

The instructor was an older lady who arrived at the school in a little blue VW Beetle, and while in class I could hear her coming because of the engine. Out of the car came a woman in her 60s. She was dressed so colourfully, everything mis-matched, with massive sunglasses and red lipstick. I didn’t think she was a teacher at first, and wondered who she was and why she looked so weird.

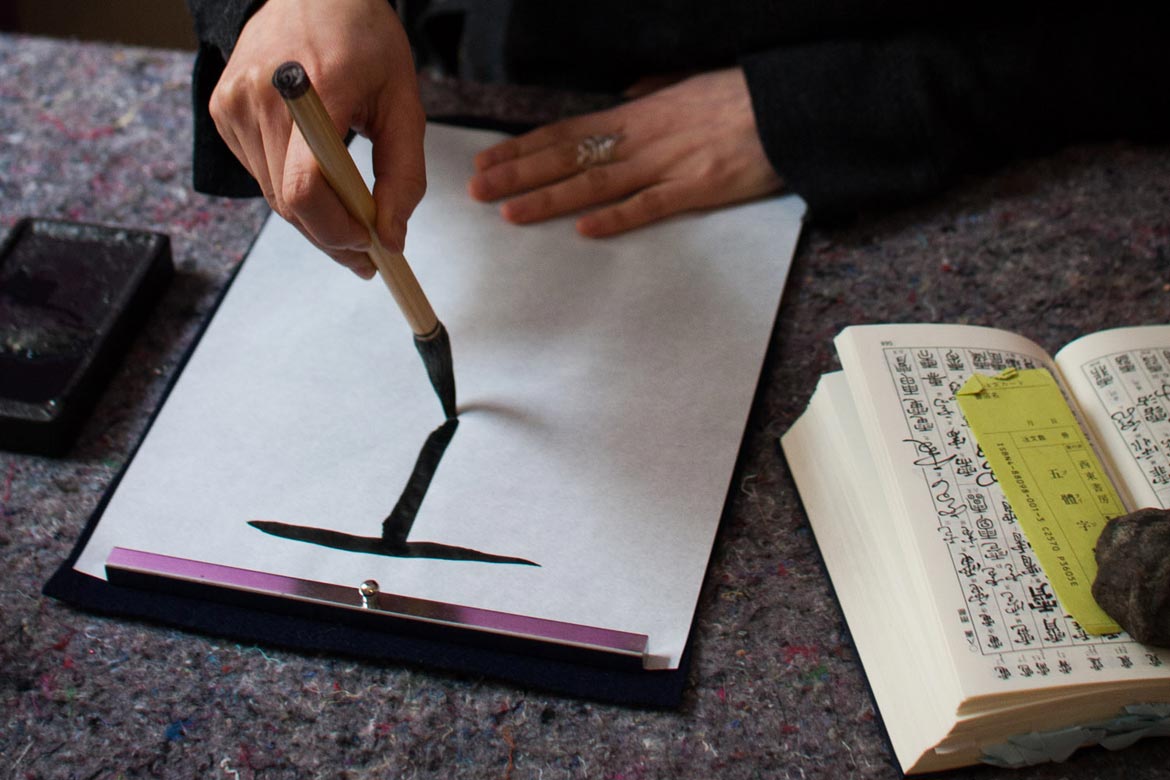

The way she taught was also funny. She always came with a bucket full of water and a massive brush, and she would clean the blackboard and write with the water. Every week she would pick some kids to the front and write. It was so interesting, so dynamic and exciting.

I thought it was cool and really liked it. So after sixth grade, I told my father I wanted to continue. He found a teacher near my house, and I started learning with him. He was also quite easy going—he cared about the details, but the main thing for him was to always be genki, “Just write genki!” I would worry about making mistakes and he would say, “No no, don’t worry about that, just write it.”

Why did you move to Berlin?

I always wanted to live abroad, and after university saved some money to go away. When I left Japan I lived in London, then Sidney. I really liked it but felt really far away from everything. So I decided to move to Madrid, and spent nearly five years there. I arrived during the big financial crisis, so people were losing their jobs and were a bit on edge.

I was very stressed, and started losing more students every year, so I thought it wasn’t good for me. My partner was also tired of living in Spain, and found a job in Berlin. So it wasn’t my choice, actually. But when I started researching the city, the condition for artists looked not so bad, and I thought I could try a few years. Then I liked it, and have been here since 2012.

The funny thing is that I studied German at university because the other option was French, which I found impossible to pronounce. I thought German sounded easier. But it wasn’t (laughs). I studied but figured I’d never use it. Calligraphy was for old people

Have you always taught shodo?

I actually started teaching in Madrid. Before that I never thought anyone wanted to learn shodo. Even in Japan, all my friends said, “Why do you want to do calligraphy? It’s for old people.” It actually was, at that time, but I liked it.

When I moved to Madrid I met a guy who owns a karate dojo. I went there to be a Japanese language teacher, but when he saw my CV he was surprised to see I was a calligrapher, and asked me to teach calligraphy instead of language. That was the beginning.

How did you start Sosekido?

I thought: Okay I have students, I have a class, now I need a website. A friend was doing a website for me and asked, what do you want to call it? So I needed a name. I really liked the way my teacher taught me. At that time I didn’t think he would die so soon. I thought it would be nice if I could carry on his way of teaching, so when we met the next time I asked if he would mind me using the same name. He said, “Of course not.” Quite soon after, he died. So for me, it was good that I asked.

Now in Berlin I teach all ages. I have one boy who started alone when he was six years old, and this May he’ll be 12. Then there are people around 30 years old, and around 75 or 80. The good thing about my class is that these people, all of different ages, are like a team—I always call them a team, not students. Outside of class I think they also hang out, invite people for tea or whatever. Most of them are German, though there are also people from places like Poland. So it’s pretty mixed.

What is it like teaching to people who don’t know Japanese?

For me calligraphy is about movement and respiration—you can call it like a meditation if you like. It doesn’t matter if you actually write the word, it can be just drawing lines using a brush and ink. What I always tell people who visit my exhibitions is, “[the characters] look like a picture. One part is very dark, one part very dry. Or this part is very curvy and this part very straight. The combination of those lines, do you like it?” It’s more like an abstract drawing.

I don’t really focus so much on the language itself. It doesn’t really matter at the beginning, but over time most students become interested. One girl I teach was looking for European calligraphy, but somehow found my website and gave my class a try. At the beginning she was good, but wasn’t really trying to understand the meanings. Then at one point she realised that if she knew the meaning, she could put more feeling into it and maybe change her way of writing. So I think they naturally find their own reasons why the language is important. They’re not here to learn language, and when they show interest I think that’s enough.

Copying is boring

Has teaching non-Japanese taught you anything about the art?

Yes. It has to be art instead of learning the kanji. There is also shuji, or learning characters, which I think outside of Japan or Asia is difficult to teach. In Japan it’s typical for a teacher to have students copy an example several times, then she checks and picks out the ones that are wrong. But she doesn’t explain what’s wrong, and the student returns to their seat and thinks, “Why?” This is not the way of thinking that works here. The mentality is different.

So I give students an example for a character each day, but tell them I don’t want them to copy it. I explain what the word is, and it’s up to them. The goal is to find your own way of writing—more like shodo (way of writing)—especially in Europe. In Japan it’s more important how good you can copy the example, but for me that’s boring. For me, the “correct” way doesn’t exist. It’s the same as life—what’s correct? Correct for you, but not correct for me.

I think in shodo, the most important thing is the balance of the character, not the ‘correct’ way. So as long as a character has a balance, I think it’s beautiful.

How has living in Europe changed the way you practice shodo?

Up till the end of last year I never had contact with any Japanese calligraphers, so I kind of forgot how it was in Japan. In a way I was free to do anything because there’s no right or wrong. Then last year a Japanese calligrapher found me through Instagram, and said, “What you do is actually very close to what I want to do.” She was in Japan and thinking that we have to get out of this “right way” of doing things. You have to have fun. So I decided to join their group, Mugen Mirai.

I went to Japan in September, and met other calligraphers for the first time in my life. Listening to them talk about the Japanese calligraphy world made it feel so heavy. The tradition, the hierarchy, everything. It felt like too much, and I couldn’t cope with that. So I’m really happy to be outside of Japan, but still promoting this Japanese art in my own way. I think that’s the big change, but it just happened because I didn’t know.

Some kind of Storytelling

Is there a movement in Japan to bring shodo into a new era?

I think so. Mugen Mirai is more focused on kids, for example. And lots of workshops use ancient characters instead of traditional shuji ones—more like abstract pictograms. I really liked this idea. In this way, people here can also learn how kanji developed. We have an exhibition on 1st February that uses these ancient characters to tell stories—so it’s called “Storytelling”. I found that my students are very keen on it, and they can actually feel more familiar with the character than with traditional techniques, because it’s like a picture. If it’s a mountain, they see the mountain, and they really like it. In Japan, Mugen Mirai is using these characters to promote calligraphy to more people in general.

You participated in NION Week, but what other kinds of projects do you do outside of Sosekido?

I always like performing and collaborating with dancers and musicians. I’ve done some performances with Japanese contemporary Kazuma Glen Motomura here in Berlin. I’ve also performed with an experimental music group—I just happened to be there and it was an interesting and fun experiment. It was the first time for me to have no plan; I was told it would last around 30 to 50 minutes and I could do whatever I liked. The music was also improvised so nobody knew what would come out. It was like, suddenly a dancer would come stand on the paper, and I couldn’t just stop writing, so I had to pretend everything is normal and started writing on him. It was a very new experience for me, but I liked it.

My students will also participate in an exhibition in Japan with Mugen Mirai in Ibaraki. There’s a space centre in Tsukuba, so the theme is related to space, but using the ancient characters.

I also really want to teach more kids. My project this year is to teach Japanese or half-Japanese kids born here in Germany who are at risk of forgetting their Japanese. I want to make a class especially for them.

It must be interesting for a Japanese or half-Japanese person to explore their own culture together with non-Japanese people.

I really like my team and learn a lot from them. Three members are learning Zen meditation, and can recite the Heart Sutra without looking. I don’t even know it! (laughs) They even go to a retreat every year for a week or two. I never did proper Zen meditation, so for me it’s really interesting and I can ask them a lot of questions. They’re my inspiration, and that’s very important for me. They inspire me to learn more about Japan, for example, by bringing things that they find to me and asking questions.

They always give me some hints, even the kids. Kids write a certain way and I think, “Oh, that’s not right.” But then, why not? It looks good. For them it looks like what it does, an elephant or whatever. And it changes the way I look at the characters too. I think they help me to be free.

Juju Kurihara runs the Sosekido school for Japanese calligraphy in Berlin.

The school’s exhibition “Storytelling” opens on 1 February at 19:00, and runs from 1-7 February at the Atelier für Photographie in Prenzlauer Berg.