Wabi-Sabi is one of several concepts that deal with aesthetic perception and sensation in Japan. Although it describes the beauty of the simple, modest and naturally aged, nowadays industrial manufactured products have appeared. Is this Japanese culture taken ad absurdum?

I’ve been thinking a lot about Wabi-Sabi in my life. In particular, I was thinking about one question: which highly educated and culturally experienced person would be able to write a good and understandable summary about it? I always get pretty much nervous when I am asked to talk and write about Wabi-Sabi. But who? Who could do it?

Knowing about my limitations in understanding Wabi-Sabi, I set out many years ago to talk about this concept with Japanese artists, professors, and in any case people with a deeply rooted cultural understanding. What answers did I get? Humbleness. Wabi-Sabi is a very complex subject, nobody can explain it properly. Maybe you can only feel it anyway. “Oh, Wabi-Sabi is…”

Well, and now I’m supposed to tell you something about it. In the face of this challenge, there is basically only one thing I can do: to shed my shyness and just share a few naive thoughts and impulses with you. What do you get out of it? A little bit of inspiration. At least this is what I would really love to share with you.

So what is Wabi-Sabi all about? Generally speaking, it’s one of several concepts that deal with aesthetic perception and sensation in Japan. And aesthetics, I can tell you, is nothing trivial in Japan.

A bit of background about wabi and sabi

It all begins with two words – wabi and sabi – and both have a long tradition dating back to the 15th and even 13th century.

The present meaning of sabi can be derived from different terms.

sabu – to slacken off, to disappear

susabi – can mean desolation

sabiteru – to become rusty, to age.

sabishi – lonely

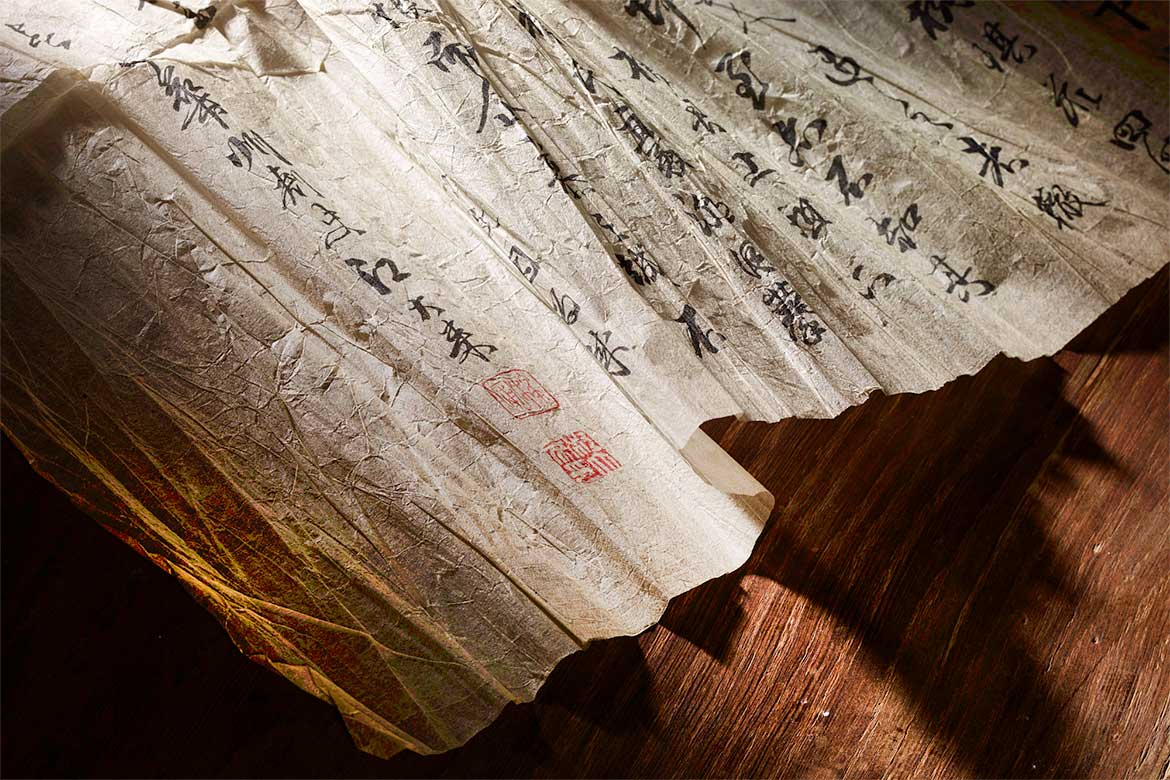

My personal association with sabi is the term “traces of time”. It refers to those traces that time causes on the surface of an object or material, e.g. rust, weathering or staining. Admittedly, at first glance these words don’t reflect anything aesthetically pleasing. Rather, they give the impression of something poor, sad and ugly. Indeed, Japanese literature very often spoke of desolate and lonely feelings, e.g. in 11th century. Over time, however, theorists developed a related approach that was explicitly associated with beauty. Objects slowly dwindling and aging were ultimately associated with greatness and beauty.

From an aesthetic point of view, the present meaning of sabi comes along with something old and worn out with patina and little damages, but also with maturity. We are talking about the beauty of those things that show the traces of life.

The term wabi? It derives from vague or lost. Suzuki Daisetz, a highly quoted interpreter of Zen Buddhist principles describes wabi as the aesthetics of poverty. Again, this sounds rather terrible as pleasing. But, combined with the Buddhist idea of satisfaction with the little and the renunciation of materialism and consumption, again, this idea has a positive meaning. Besides, wabi contains the syllable wa. It means harmony, calmness and peace.

wabi deals with simplicity and authenticity. It goes hand in hand with the beauty of unpretentious things and with imperfection. And it is related to natural or at least organic looking things and interiors as in Japan harmony goes hand in hand with nature.

Everything is transient, nothing is finished, nothing is perfect

To sum it up, Wabi-Sabi describes the beauty of the simple, modest and naturally aged, in other words, transience. But – and this is perhaps the most important thing – Wabi-Sabi has nothing to do with renunciation or sacrifice. It’s about a much bigger idea – it is about harmony.

The visual epitome of Wabi-Sabi is the simple and irregularly shaped Raku tea bowl or other glazed stoneware that is highly appreciated in the tea ceremony. But also simple tea ceremony instruments made of bamboo and iron reflect this concept. Nothing is polished and exaggeratedly shiny, nothing is perfect. Also simple tatami rooms having an even sober appearance show the Wabi-Sabi spirit. In terms of fine art we are talking about simple Zen paintings or calligraphy. Do you have these pictures in mind? Then here comes the twist.

It happened that I really had to laugh when I met Wabi-Sabi for the first time in Munich, namely in a relatively fancy furniture store. The same thing happened to me in the household goods department of a department store and in the gardening centre of my DIY store. Lifestyle magazines announced Wabi-Sabi as the new trend of living and every simply crooked bowl was suddenly called Wabi-Sabi, even if it is basically an industrial mass product.

Is Wabi-Sabi really a trend today? Like Vintage or Shabby Chic?

Well, that is the big question. And it is certainly up to us to evaluate it. Maybe you like the idea of Wabi-Sabi being a trend, as long as someone cleans up with boring round plates. Or you completely disagree, as an industrial manufactured plate, regardless how crooked it is, will never be Wabi-Sabi. That is Japanese culture taken ad absurdum.

As I said, I was just laughing. I’m not a dogmatist, but Wabi-Sabi produced by pushing the digital button really seems to be funny, as it is obviously a contradiction to the historic spirit described above.

Does that mean that new things can never show the spirit of Wabi-Sabi? That would be presumptuous and I do not think that it is true. But the crucial idea is craftsmanship. Therefore, a new tea bowl can host the spirit of Wabi-Sabi as long as itis made by hand and if it corresponds to the principle of beautiful simplicity. Even a newly built house can be built in the sense of Wabi-Sabi if simple, natural or old materials are used.

However, craftsmanship is crucial because one thing is immanent to it: it requires practice, time and a close connection to the real world. In fact, Wabi-Sabi is the epitome of “connection to the real world” and thus the compelling antagonist to digital reality. Koren describes this as follows: “Digital reality … only exists if someone actively generates it ….” Every digital aspect must be encoded in a binary structure of “one” or “zero”. “Between one and zero is nothing. But Wabi-Sabi is located exactly in this infinity between one and zero.”

But, back to the question of Wabi-Sabi being a trend. I hope that one aspect about Wabi-Sabi became very clear now. Wabi-Sabi is an abstract concept, something that requires more than “seeing” or “understanding” – something between zero and one. For us, the viewers, this comes along with a real challenge: it means that we have to open our senses to recognize the extraordinary that we would normally miss. Wabi-Sabi objects, interiors or gardens will never try to catch the attention or emotions of the viewer. Wabi-Sabi “simply comes along”. However, this is not an ideal constellation to sell a product. If something is hard to spot, it is even harder to sell. Therefore, real Wabi-Sabi is far from being a marketable trend.

Does that mean that Wabi-Sabi can ultimately only happen in Japan? Wabi-Sabi has its roots in Japan, but I am sure it can be experienced everywhere where simplicity and the sense for nature work together. The beauty of simplicity is certainly not bound to any country.

International Wabi-Sabi interior design

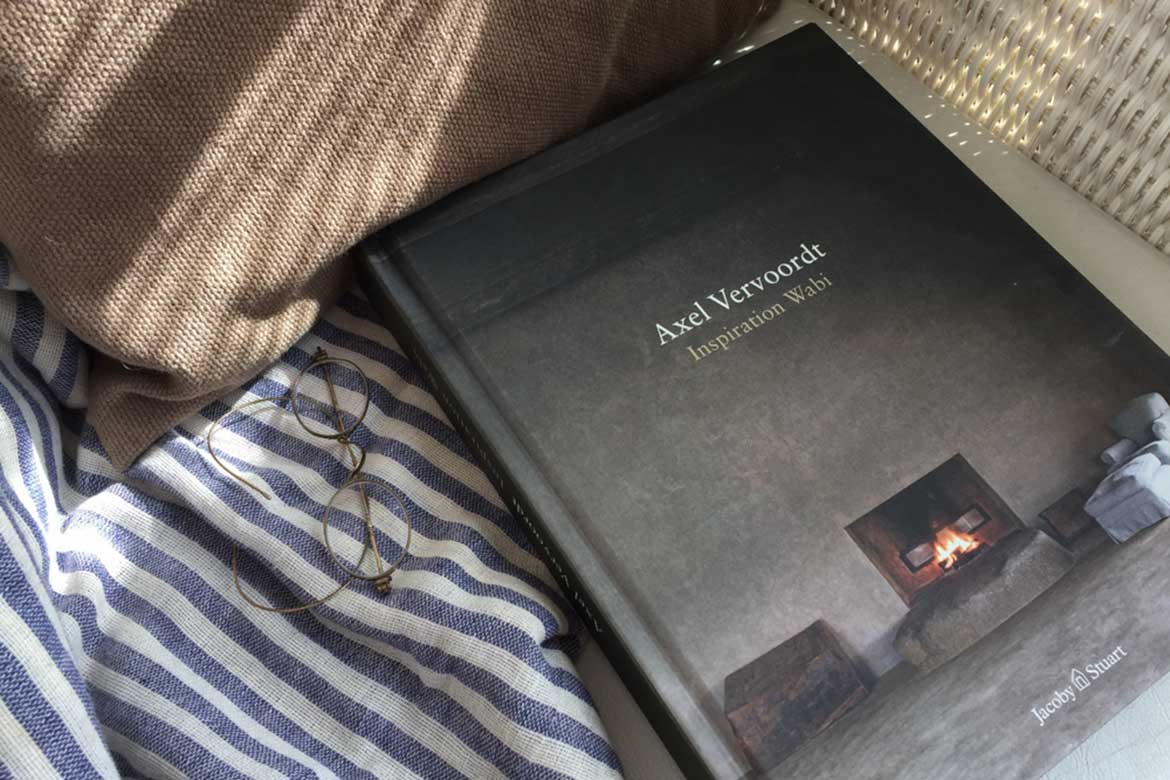

Someone who creates Wabi-Sabi interiors like no other (and he is not Japanese!) is Axel Vervoordt. Yes, he creates Wabi-Sabi but he does not imitate it. He studied the concept of Wabi-Sabi in Japan and lives the principle in an almost spiritual way. Axel Vervoordt designs houses in Japan, in his hometown Antwerp and in different regions of the world. And he knows how to integrate an important aspect: emptiness. His book Wabi Inspirations is a tribute to Wabi-Sabi. I am sure after reading this illustrated book, which also contains very concise texts about Wabi-Sabi, you will understand the world a little bit better. Axel Vervoordt, one of the best ones to impart Wabi-Sabi.

Some further books on Japanese aesthetics and Wabi-Sabi

A tractate on Japanese aesthetics, Donald Richie, Stone Bridge Press 2007

Wabi Inspirations, Axel Vervoordt, Publishing Jacoby & Stuart, Munich 2013

In praise of shadows, Jun’ichirô Tanizaki, German version by Manesse, Zurich 2011

Wabi-Sabi. Woher? Wohin? Weiterführende Gedanken, Leonard Koren, Ernst Wasmuth Verlag, Tübingen/Berlin 2015 (only in German)

A much longer list is available on my artblog.