In January, NION Community members Birgit and Guillaume started an artist residency in Kyoto. Their last weeks were full of crafts, rituals and mindfulness.

Tenrikyo is a Japanese new religion believing in the “God of Origin” – Tenri-O-no-Mikoto – and has its headquarter in Tenri, Nara Prefecture. Their practices are characterised by cleaning.

They believe that “evil” is like dust on our mind and has to be swept away. Every individual is supposed to work towards a polished mind, thus against the accumulation of dust. Dust is metaphorical for wrong thinking and acting, and god as a “broom” can help to remove these residues.

Practitioners of Tenrikyo apply these believes literally and clean in and around the temple continuously, but especially before early morning and evening services. Dust is wiped away from every possible spot, the floor is then swept and finally polished with a white towel.

Crafted Brooms

Even though not everyone might agree that “god” can be compared with a broom, Japanese crafts tradition in broom making is very unique and of exceptional beauty.

Our love for Japanese cleaning tools started at Naito, a brush shop in the city center of Kyoto.

The store is located next to the Kamo River where it has been for over 200 years. It was founded in 1818 by a family descended from Samurai. All items, from brushes to brooms are hand made by skillful craftsmen from Wakayama Prefecture – some specifically and exclusively for their store.

We had the amazing opportunity to interview the owner of the store, a wonderful old lady, who incarnates the 7th generation at the head of the family run business.

Tradition and Sustainability

Tawashis are typical scrubbing brushes in Japan. They are manufactured for centuries from an organic material, a windmill palm tree called shuro.

It is a tall evergreen palm with an elastic and highly water resistant bark. While the tree itself grows in Japan, in the last years the material has been mainly imported from China, due to the decrease profitability in harvesting it locally and the increase in plastic products.

We visited 中西富一工房 to get a better insight into their origin and production. The company recently started new collaborations in order to cultivate and harvest shuro locally again, making it a very eco-friendly product.

But not only Tawashis are crafted from shuro, also wonderful brooms. We hope to be able to collaborate with one of these craftsmen in the near future.

Gardening

Tools are objects which do not belong to the body, but they allow us to extend bodily functions in order to achieve an immediate goal. A broom is exactly such a “body extension” which enables us to clean our environment. So how does it feel to create such a body extension?

Guillaume had the opportunity to participate in a bamboo broom making workshop, guided by the gardener of the Murin-an garden in Kyoto.

It is very common for gardners to create their own tools. Depending on the surfaces they clean – being it moss, gravel or concrete – these tools have to have different properties in order to make the task efficient and convenient. Gardeners, being the experts, know exactly what they need which allows them to create brooms fulfilling these specific functions.

Guillaume and I were able to clean and to try out our new tools at the Murin-an garden, in the early morning hours before the garden would open to the public.

The place itself is a cultural monument. Its elaborated design plays with perspectives, evoking feeling of depth, revealing new atmospheres and scenarios when strolling along its winded path.

While cleaning we were allowed to leave the trail. The different types of moss – long, short, dense, fluffy, bright or dark green – where not only pleasing to the eye but felt soft, like a carpet, under our feet.

A water stream, narrow and wide, winding through the garden constantly changed the sound atmosphere. Close to the waterfall, at the back of the garden, one was fully immersed by it.

While removing carefully one by one each leaf that had fallen down, the mind drifted off in tranquil peacefulness. In a meditative state, time disappeared leaving one in the moment.

Guillaume later told me that it made a real difference for him, to have cleaned with a tool he had crafted himself. Analysing its properties, thinking about adjustments which could be made, he engaged in a dialogue with the object.

The last two pictures and the header picture of this article were taken in the Murin-an Garden.

Cleaning as a training of the mind

Cleaning can be much more than a “peaceful” activity. Cleanliness is an expression of respect for oneself and others. As a mediator of interpersonal relationships it is an important part of school education in Japan. The aim is to teach the students through cleaning that they can improve their environment and that it is good to do something with and for others.

This tradition is held in everyday working life, because very few companies employ cleaning staff. Rather, it is the task of all staff members regardless of their position. The aim is to improve teamwork, to train their attention and to promote consideration and independence through this routine morning activity.

To be able to understand the practice of cleaning and its influences on the mind I stayed four days with monks at the Eihei-ji temple.

Eihei-ji (永平寺) – “temple of eternal peace”

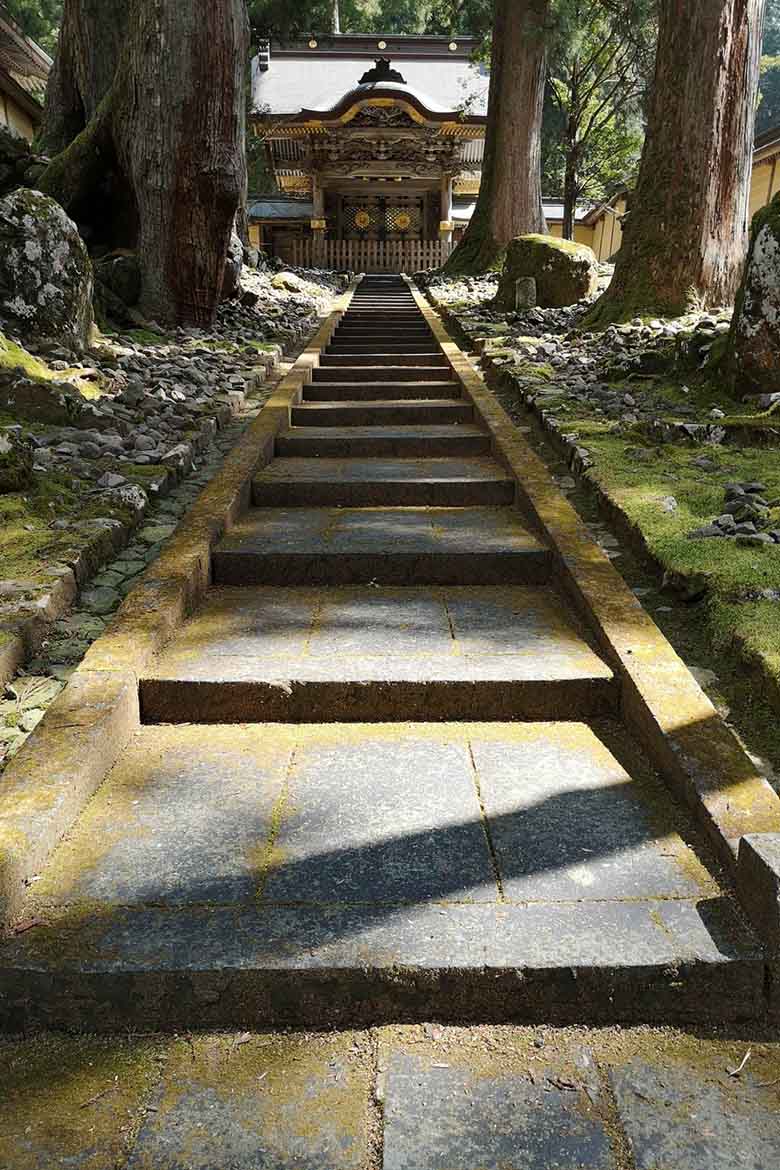

The rural monastery Eihei-ji is located in the Fukui Prefecture and was founded in 1244.

Spread over a hillside, the complex is surrounded by cedar trees (some of them up to 30m tall and as old as the temple) and bright green moss-covered boulders.

It is one of the two main temples of the Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism. Its founder was Eihei Dōgen who brought Sōtō from China to Japan during the 13th century. Dōgen’s writings, Shōbōgenzō, include chapters on toilet manners, bathing and the important role of the kitchen. These rules are still practiced and part of the training of monks.

About two hundred monks are in residence at this main temple. Their training can run for one to many years, none of them knowing when their teacher will decide that they are ready to leave. Withdrawn from the outside world, without contact to friends or family, they undergo a strict rule based teaching practice. I feel honoured and thankful to have been able to stay with them, to get a glimpse into their daily life.

Upon arriving each participant had to hand in all of their valuable items, digital devices or cosmetic products. It was probably for most of us the first time in years that we had been without any contact or distractions from the “outside” world for longer than one hour.

After a short welcoming and general introduction, we received guidance into the daily routine and practice which is done according to fixed rules ranging from “how” to go to the toilet to eating.

The following days, without pronouncing a word, we did perform these activities in synchrony, harmony and silence – allowing each of us to be in the moment in total self-awareness.

The day would start at 3:50h with 45 minutes of zazen (still sitting in a lotus position facing the wall), followed by the morning service in the hondo (main hall) with reading and chanting sutras.

To reach the hondo from the sōdo (meditation hall), we had to walk through the whole monastery – a traditional Japanese architectural structure, half indoor half outdoor, connecting buildings. Wearing only a few layers of cloth, socks and slippers, the cold soon got to our bones. While the surrounding forest, half covered in fog, would slowly awake with the sunrise and singing birds.

Around 7h we would receive breakfast – a warm bowl of rice porridge. Nothing would be left over and nothing would be spilled. Everyone would receive hot water to rinse their bowls, which even had to be drunk. We would continue the day with cleaning all spaces, from the tatami room in which we slept to the bathroom and toilets.

We did seat for zazen about 5 to 6 times a day. Without moving, in total silence, one would undergo various stages of experiences. From time to time thoughts would be overwhelming, coming from nowhere, steering up memories which would take all mental space.

Seconds later the direct surrounding would rise back to a full awareness. The sound of the water from the river outside, somewhere a few hundred meters away, would catch your attention as if you were right next to it. But the most dominant sensation was pain, specifically in my legs. Statically folded they would be slowly falling asleep while pressing persistently on the tatami mat. Accepting the pain just as what it was, a sensation, was one of the most enriching experiences which lead me to a moment of real peace with myself.

Even though meditation or zazen is what most people praise as a way to mindfulness and self-awareness, I learned during my stay that all our actions can and should be treated with the same awareness. To clean or to eat was as much “zazen sitting” as it was to dedicate your mind and body to do nothing. And while my small “breakthrough” of finding peace in pain was enriching – the discoveries I made during silent dinners and dedicated group cleaning activities stayed with me the most. These daily routines taught me about myself in relationship to others and my surrounding, connecting body and mind. Rather than being isolated, as one may feel in meditation, I felt connected and became aware of these connections.